That we only have one life on this planet, and that that life is short, fragile, and necessarily limited by the circumstances into which it was born, is a fact known to everyone, never mind our skill in self-deception or our success in self-distraction. Everyone longs for a longer life, a wider life, a life less narrowly hemmed-in. Even the person perfectly content with her life, if any such person exists, finds herself cast out, sooner or later, at least for an hour or so, into that barren wasteland of the imagination which we call boredom. What we are able to experience over the course of a single life is vast, to be sure, and yet something in the human heart, ever restless, ever roving, ever seeking and searching and questing and exploring, will always want to widen that circle of experience, like a lake wanting a stone to ripple its still surface into ever wider rings.

Other people’s lives often look more delightful, more fulfilling, more interesting, more adventurous, more bathed in a strong ferment of good luck than our own—they may seem to have more money, more friends, more sex, more love, more “more.” But we know intuitively that were we to divest ourselves of our selves and actually step into the life of that other person, so rosy, so charmed, so picturesque from the outside, it would offer to us an equal share of pains and torments, foibles and misfortunes, social gaffes, daily aggravations, dreams unfulfilled, hopes dashed, loves unrequited. The grime would show on the porcelain, and the sparkle would dull. Even a single speck of dust is enough to dash one’s illusions and topple shining palaces in the clouds. A dress in a catalogue looks beautiful to wear, and yet were one to actually have it and put it on, it might bulge here and squeeze there; it might offer up to the world some unflattering insinuation of unexercised flesh normally kept undisclosed; one might be prevailed upon to go out and buy new undergarments for it; it might itch; over the course of the day, it might crease; one might grow paranoid over the possibility of its staining or spoiling, which would subsequently stain and spoil one’s own enjoyment of wearing it.

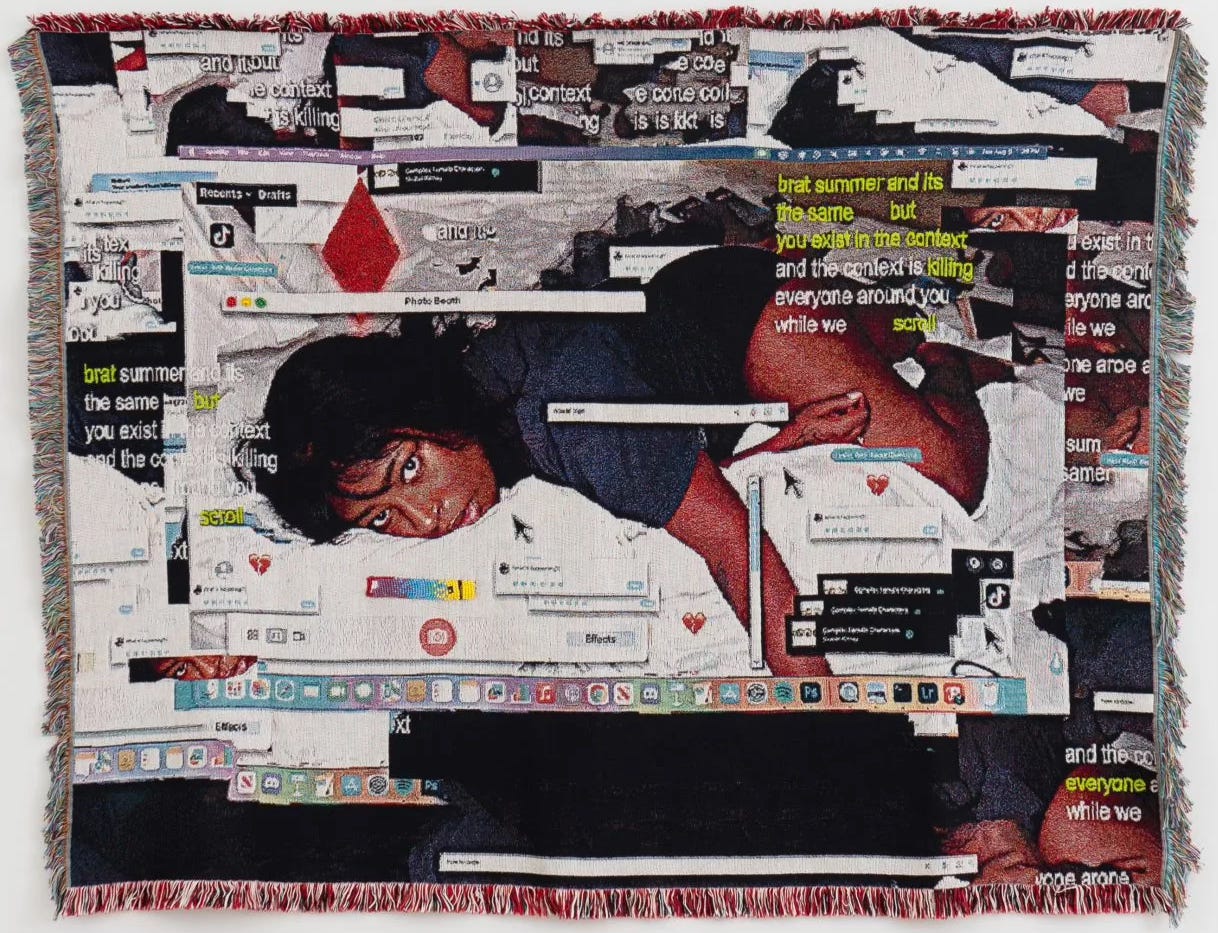

On the whole, everything is better in the imagination. To live through other people and yet be safe and dry on the shore of oneself—to look out of the plane’s window, see a bird, and soar and veer with it, spreading one’s wings and triumphing in the exaltation of flight, and yet be fastened securely with a seatbelt, not actually exposed to the elements, is a pleasure unmatched by little else. “O thou the leader of the mental train: / In full perfection all thy works are wrought,” writes Phillis Wheatley in her ode to the imagination. To live through other people is the backbone of fiction and the animating impulse of social media—for indeed social media offers to us a kind of fiction of people’s lives, and one must remember that the early novels presented themselves as biographies and autobiographies: the first edition of Robinson Crusoe credited Crusoe himself as its author, complete with an editor’s preface that described the novel as “a just History of Fact,” and even over a century later, Charlotte Brontë kept up the jig when she gave her novel about the life of an English governess the full title Jane Eyre: An Autobiography. Who would really like to have a childhood of bullying and beatings, loneliness, deprivation, disease, desolation, only to find, after wives in the attic and wanderings across moors, love with a strange man? But in the reading of it, nothing is more delightful, and that proposal scene in the garden, with its sudden rain and the tree split by lightning, is more vivid to me than many of my own memories.

People blame the vicarious pleasures of social media for a host of modern ills, just as novels were once blamed for filling girls’ heads with stuff and nonsense, but I say, let us always be curious about the lives of other people. If this curiosity can be properly steered between the Scylla and Charybdis of, on the one hand, the sort of negative comparison that leads to either dejected self-pity or supercilious self-aggrandizement, and on the other, the delusional reaching after impossibilities that leads to false hopes, false appraisals of self, disappointment, and the wastage of enormous sums of money—if it can be maintained without being tainted by spite or envy or bad feeling, keeping itself in a strong and healthy current, then it serves only to enrich experience and give one a broader vista of life. It creates doors in the narrow room of one’s existence, passages and corridors, zigzagging staircases, wardrobes leading to Narnia.

Let us always keep a little of our nosiness. I always enjoy reading the little restaurant reviews that appear in the front of the print editions of The New Yorker, never mind that I will never set foot in many—or any—of these establishments. Every week when it comes in the mail, I flip eagerly to that page, where a description of some fascinating temple of food sits beneath a beautifully photographed plate of frogs’ legs or oysters Rockefeller. I don’t live in New York, nor do I have any intention of doing so in the near future; in my day to day life, I care little for food, eating to live and not living to eat, and I lamented deeply when the The Best American Travel Writing was cruelly sacrificed on the altar of The Best American Food Writing—the pleasures of the gourmand are not mine—and no matter how appetizing frogs’ legs look, I don’t think I shall ever partake willingly of that delicacy. Nevertheless, reading these reviews, I find endless delight in imagining myself there in the cozy atmosphere of some tucked-away joint, savoring the taste of some fantastical dish.

I like to imagine a dream double of myself, and it is her I send off to distant lands to meet distant people and wander distant streets, her whom I cast into the past or into the future, her who I dress in glittering silks or daring skirt suits, Schiaparelli’s spring collection or vintage McQueen. Then she comes back to me, her eye swirling with images, her head full of stories, her heart “with beaded bubbles winking at the brim.” It is well that I have her—her suitcase is always packed, she is prepared for any journey. She has learned from Ovid how mutable form is, and she slides easily between worlds, donning and doffing experiences the way one changes clothes.

Since taking up residence on this planet, I have lived approximately 1,356 weeks, and a couple of years ago, I spent one of those 1,356 weeks entirely consumed in those “What’s In My Bag?” videos. This fact causes me no regrets or compunctions. I relish that week thoroughly. From the contents of these women’s bags, it was possible to reconstruct a whole life, as archeologists have resurrected our distant ancestors’ daily doings through their material possessions. What would it be like to go about life with this lipstick in my makeup case or that notebook and pen? What sort of person would I be if I had that phone case or used that lip balm or carried those sunglasses around with me or put hairpins in a little Altoids tin or read that sort of novel on the train?

In the handbag of my vicarious living, I have collected mother-of-pearl powder compacts and Victorian coin pouches, “the saint’s sighs and the fairy’s cries.” Now and then I might rummage through it, resurfacing memories I never lived, strange portals, fantastical doorways. Why hanker after immortality when it is already at our fingertips? So little time is allotted to us, but knit another life into your own, and vast pockets are created, years added, time gained. Seek no other elixir but this, no fountain or peach.1

Dear Readers, I’m sorry I haven’t posted in a couple of weeks—certain strange events have transpired in my life, but a Friday post will be coming, so watch out for that later this week! Meanwhile, I hope you enjoyed this little essay—I want to try to post more essays or other sorts of pieces—and if you did, please like this post, share with a friend, or leave a comment, as I always enjoy hearing your thoughts.

The idea of an “elixir of immortality” has existed in various cultures and times, the idea of a “fountain of youth” was first recorded by Herodotus, and the Peaches of Immortality have symbolized longevity in Chinese mythology and art.

This is beautifully written—thoughtful and expansive, yet intimate in its wonder. The way you capture the tension between longing and reality, between imagination and lived experience, is mesmerizing. 🚪☁️🍑

Vicarious living is one of my favorite flavors of dreams! You perfectly capture that feeling here.