Friday Frivolity no. 3: The Beautiful Violence of a Summer Storm

poems of force // 7-meter-long beds, Godard, and the sea // classical music recs for summer

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you’ll get a short essay, plus a moodboard, 3 things I’m currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I’ve been reading lately, a little shimmer of poetry, a “beauty tip,” and a question to spark thought.

—

The Beautiful Violence of a Summer Storm

How much violence is required by beauty? Think of Helen, think of the army of black ships crossing the wide salt sea, think of the fleet-footed soldiers, think of the flaring of the horses’ nostrils and the kicking up of dust beneath their hooves, think of the bodies, bleeding out, carrion, their souls already taking one step, then another, irreversible, into the halls of Hades, think of “the topless towers of Ilium,”1 burning, think of the wailing wives, their cries of lament billowing up to the gods, think of a summer storm.

It is, as Simone Weil called the Iliad, a “poem of force.”2 There is something in the air that builds to a boiling point, then breaks. The heat of it becomes unbearable, unendurable, something terrible. “Poets are always taking the weather so personally,” said J. D. Salinger, or one of his characters. But could nature have provided any better correlative for human emotion? Aren’t emotions simply internal weather? Sometimes it’s sunny, not a cloud of melancholy or malaise in sight, true blue skies for miles, the birds singing, the full leaves turning their green cheeks to the breeze. Sometimes things are overcast, and our head bows and our feet drag in a dreary atmosphere of grey; sometimes solitude comes like a little snow; sometimes there is a small weeping, gentle, almost sweet, the sweetness of the heart’s pain, “il pleure dans mon coeur”; sometimes a curtain flutters in the soul and brings with it the perfume of lilacs from the garden.

Then there is the fact that people, like countries, have their different climates. Some give us whiplash with their vicissitudes, while others are seasonless and tropical, generally sunny, cheerful, unbothered—strange to those of us who are all rainbows one moment, thunder the next. To come to an understanding of someone demands a meteorology of their internal weather patterns. As we grow older, we evolve from the rusted weathervanes of youth and antiquated rain buckets to sensitive radar, lidar, satellite. Perhaps, if we are lucky, predictability becomes possible. Some of us, alas, become storm chasers.

All repression demands release. There is no strong feeling that does not require some physical or verbal manifestation. However much, all the year, I long for the warm, sunshiny days of summer—the days of sundresses and sunny outings, family trips to the Cape, picnics in the backyard—I secretly long all the more for their more delicious alter ego, the summer storm. I love the humid air, thick, tense, expectant; I love the sky’s sudden darkening, the clouds curdling and thickening, clotting together, blotting out the sun; I love the cracks of lightning like Zeus’s whips, the thunder rumbling like a god’s stomach; I love the sweet release of rain, the skies unbinding themselves at last, the coolness of the first drops; I love then how it all comes down at once, too much, so much you wonder whether there’s earth enough to hold it; I love the trees bending to the lashing winds, the water rushing down the streets in rivulets. Here, finally, is a beauty that knows passion. It is like the violence of dragging wordless thought into speech.

A few days ago I went to a baseball game. It was so hot, we were sitting there fanning ourselves or putting our hair up, sweating, and then I saw, in the distance, under the lights, water falling down. Slowly across the field it started to come towards us. It was like how you might imagine a raincloud on a stage, drawn across by some invisible pulley. People got up all at once and started running, the water was on us, started running inside with their bags above their heads or their jerseys pulled up, the abandoned seats were already wet, everyone went home. I had no umbrella and nothing to shield myself with. I walked as slowly as I could, for it was not cold. Soon enough, I was drenched, the water sloshed in my sandals, I could hardly see for the drops on my glasses. People stood under the awnings of buildings or went into cafés. The cars sent up big sprays from puddles as I waited at a crosswalk. Ah, Reader, how happy I was! I took the train home; every time it stopped at a station and the doors opened, you could hear how loud the rain was, endless and torrential, not dogs and cats but elephants and hippopotami. I was alive with thrill. I splashed to the car, almost skipping.

Nevertheless, it must be said that I was more than a little content to be home. I took off my cold, wet things, put on my nice, dry pajamas, and curled up under the covers, safe and warm, with a book in hand. And the rain, of course, outside my window, now nothing but noise.

Moodboard of the Week

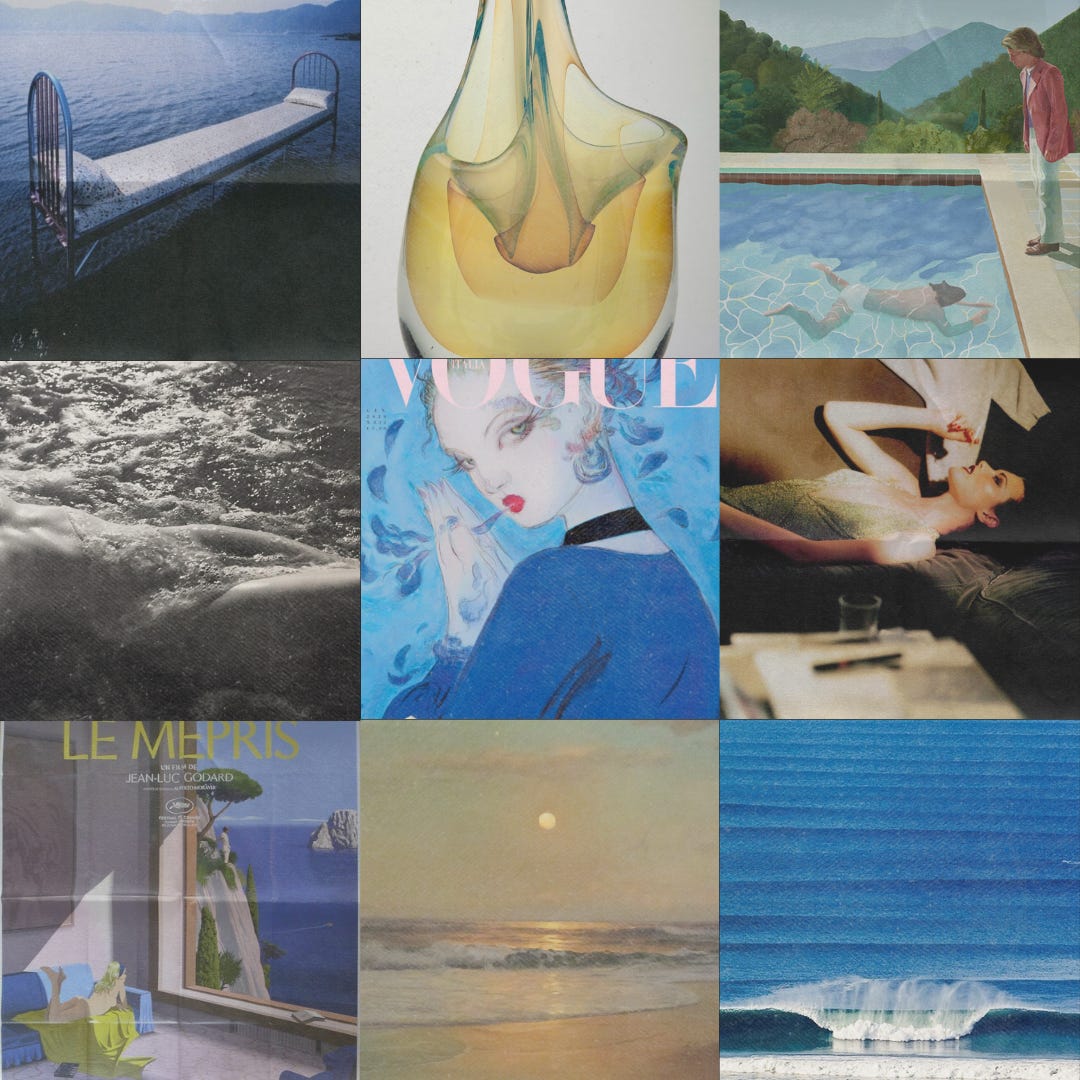

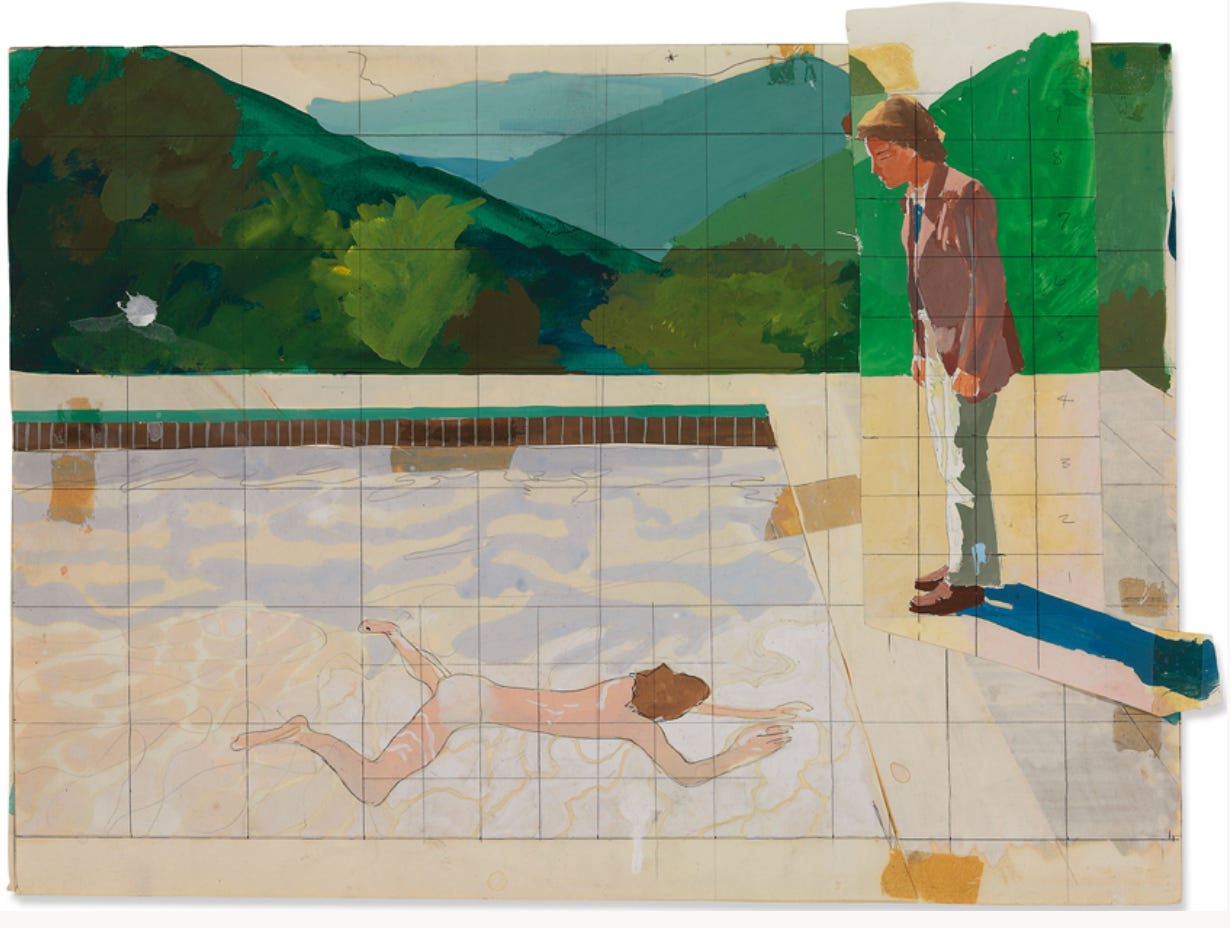

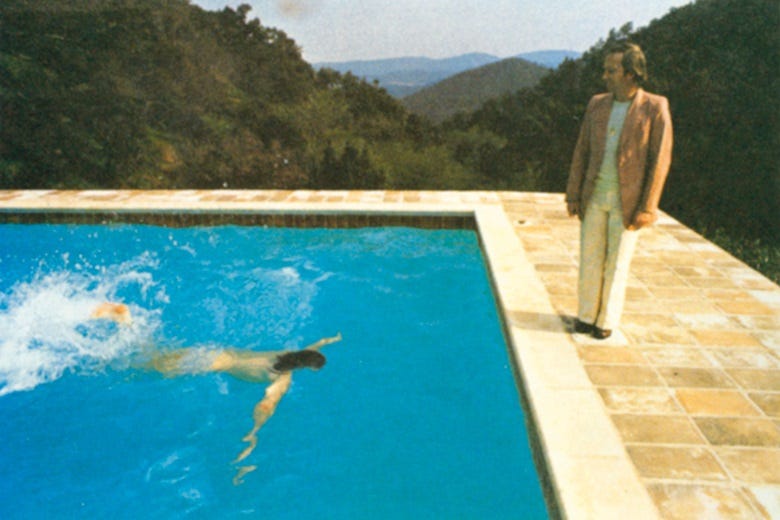

(from left to right, top to bottom)

Shiro Kuramata, Laputa (1991)—This bed is 7 meters long and is designed for two people to sleep in, one at either end. Kuramata (1934-1991) was one of the foremost designers of Japan’s postwar era and often combined influences from surrealism and minimalism to bring wonder to everyday objects. He collaborated with late fashion designer Issey Miyake to design Miyake’s first retail store in Tokyo. This is his final design, and its name comes from the flying island Laputa, from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, apt because this bed really is a flying island, levitating above the sea. “Enchantment should also be considered a function,” Kuramata once said.

Charles Wright, Opalescent Vase (1978)—I like how this vase builds up in different layers towards an inner deepening of color. It reminds me of sunlight coming through a window, the clarity of a summer morning. I couldn’t find too much information on the artist beyond the fact that he was American and lived from 1944–2016; however, you can still find some of his work being sold on eBay.

David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972)—David Hockney is an English painter who lived in Los Angeles in the 1960s, using acrylics to capture the bright, sun-drenched nature of that city. For this painting, Hockney combined two photographs: one of a figure swimming, another of a figure standing and looking down. Hockney said: “The figures never related to one another, nor to the background. I changed the setting constantly from distant mountains to a claustrophobic wall and back again to mountains. I even tried a glass wall.” He decided to repaint it right before it was to be exhibited, and finished it just the night before. Here I love how the artificiality of the pool contrasts with the nature of the mountains in the background—it reminds me a little of the pool in Walkabout—as well as the ambiguity of the relationship these two figures have to each other.

Lucien Clergue, Née de la Vague (1982)—Lucien Clergue (1934-2014) turned his lens on the rubble of postwar France, contemporaries such as Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau, and women, often rendered as faceless nudes. Née de la Vague (Born from the Wave) is a collection of photographs that clothes these women in the sea, making them Aphrodite-like figures that emerge fully formed from the waves.

Yoshitaka Amano, Cover Drawing for Vogue Italia (2020)—The January 2020 edition of Vogue Italia replaced all the photographs and editorials in its glossy pages with illustrations in order to reduce the environmental impact of its usual production: “The challenge was to prove it is possible to show clothes without photographing them.”3 The concept hearkens back to the very early days of Vogue in the first decades of the 20th century, when everything was illustrated. Of all the artwork in the issue, that by Yoshitaka Amano of Lindsey Wixson is my favorite, especially here, with the beautiful shades of blue, the dreamlike luminosity in her eyes and skin, the pouty red of her mouth. Amano is mostly known for his work on the video game Final Fantasy, but my favorite of his works is the 1998 movie 1001 Nights.

Shalom Harlow photographed by Paolo Roversi for W magazine (October 1997)—Paolo Roversi’s photography often has a softness and dreaminess to it, paired with a stripped-down minimalism and poetic intensity.

Poster by Laurent Durieux for the 60th anniversary release in 2023 of the 4K restoration of Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris (Contempt) by STUDIOCANAL—Godard was told by producers to put the famous BB (Brigitte Bardot) in a film and include some titillating shots of her: come for the nudity, stay for Raoul Coutard’s cinematography; the wonderful Casa Malaparte on Capri; the commentary on marriage; the meta-commentary on filmmaking; Fritz Lang playing a stand-in for Godard—a film director who struggles to maintain his artistic vision under the tyranny of a boorish American producer; a fake adaptation of the Odyssey that actually could be so great; Georges Delarue’s tragic score. My theory about this film is that Brigitte Bardot’s character Camille is actually a personification of cinema itself: a woman whose scriptwriter husband is disloyal to her just as he betrays his own artistic integrity, selling out to write this script that bastardizes Homer’s great epic, resulting in a tragic smash-up. Contempt has never looked so good.

Jean-Luc Godard, Le Mépris (1963) Warren W. Sheppard, Sunset with Evening Star (about 1880)4—I saw this painting at the MFA in Boston, downstairs where they have the model ships from the 1700s and paintings of ships and ships’ figureheads. Warren, who specialized in seascapes, was also an expert sailor and a designer of racing yachts. The light in this painting is absolutely gorgeous; the way it softly diffuses its light across the sky and over the sea lends an evocative melancholy to the scene.

Photograph posted by surfing-aus on Tumblr—The sea’s layers, the way the white wave chomps down like teeth, remind me of the Shakespeare sonnet that begins, “Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore.” Indeed, time marches on, the sea laps at the shore, the days heap up, “In sequent toil all forwards do contend.”

3 Things I’m in Love With

Classical Music Edition

Vivaldi’s “Summer” from The Four Seasons—I always love to listen to this when this time of year comes around for the perfect way in which it captures the sudden violence of a summer thunderstorm or hailstorm.

Arvo Pärt’s Tabula Rasa—The best way to listen to this is while lying down under the trees as the breeze and the sunlight go through, watching the leaves dance and the branches sway. On the first performance of this in 1977, composer Erkki-Sven Tüür said, “I was carried beyond. I had the feeling that eternity was touching me through this music… nobody wanted to start clapping.”5 It turns out that this music was used in palliative care for AIDS and cancer patients: they often wanted to hear the “angel music,” or the piece’s second movement, “Silentium.”6

Gwyneth Walker’s “I Thank You God”—The text of this choral piece is taken from an e.e. cummings poem, “i thank You God for most this amazing.” As a teenager, I was required to take chorus for a few years while studying the violin and piano, and though I was most emphatically not a singer and often rather shy about it, this was one of my favorites that we performed.

Words of Wisdom

Do you think that I count the days? There is only one day left, always starting over: it is given to us at dawn and taken away from us at dusk.

—Jean-Paul Sartre

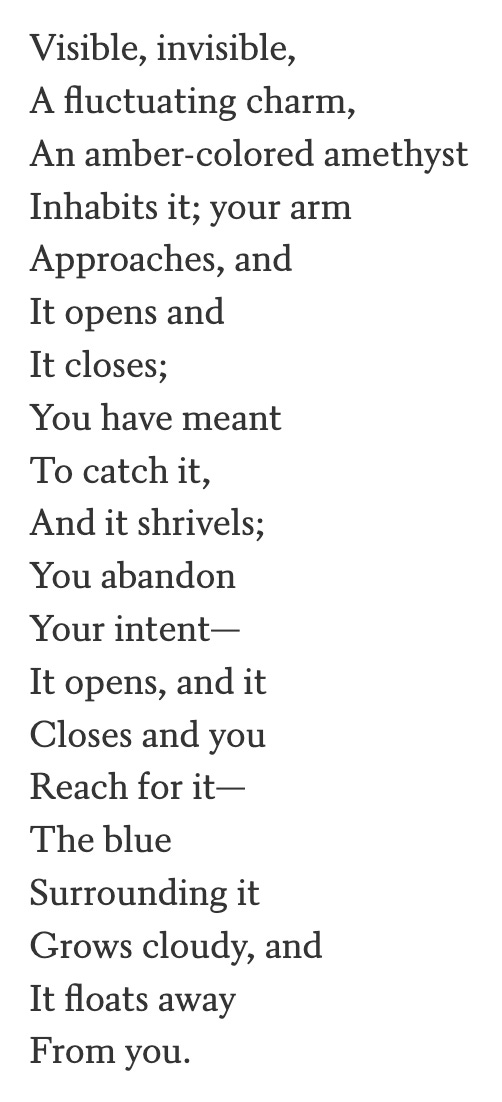

Poetry Corner

A Jellyfish

Visible, invisible, a fluctuating charm an amber-tinctured amethyst inhabits it, your arm approaches and it opens and it closes; you had meant to catch it and it quivers; you abandon your intent.

—Marianne Moore

I was reminded of this poem because of the jellyfish textile art in last week’s Friday Frivolity; it’s such a lovely, precise little poem. Moore (1887–1972) was a major American poet of the Modernist movement, although I think she’s less well-known now by a general audience. She majored in biology and histology in college, and her poetry often centers around very precise, detailed, delicate observation of animals, as well as objects and the natural world at large. She experimented with form, but unlike the rather flabby verse of today, she had a great deal of restraint, often going back and paring down old poems—the most famous example of this is “Poetry,” which she revised over five decades, controversially cutting it down from 30 lines to just 3.

This poem, “A Jellyfish,” was first published as “A Jelly-Fish” in 1909 when Moore was still in college; however, I’ve given you the edited version published 50 years later, in 1959. The most visible change is in the line breaks—the 1909 version has far more, giving it an abruptness, while the 1959 version is much more fluid, mirroring the fluctuating movement of the jellyfish itself. That the poem is now 8 lines with a rhyme between lines 2 and 4 (“charm”/“arm”) and between lines 6 and 8 (“meant”/“intent”) gives it a sense of closure and of being much more carefully composed.

In the first version, the “you” of the poem reaches out for the jellyfish twice, whereas in this version the interaction happens only once, creating a much more encapsulated moment. There, the jellyfish was “amber-colored,” while here it is “amber-tinctured”—the word “tinctured” has a precision to it that matches the conciseness of this new version, and it rings much better with the “t” sounds in “fluctuating” and “amethyst,” as well as echoing the in of “inhabits.” Both sounds predict the final word of the poem, “intent.”

Moreover, the jellyfish here only “quivers” instead of “shrivels”—shrivels is much more definite, whereas “quivers” is both more vivid and more ambiguous. A poem, like a woman, should always leave something to the imagination. We don’t need to know that “The blue / Surrounding it / Grows cloudy” and that it “floats away”—that much is already implied when we learn that “you” failed to catch it.

Beauty Tip

Make a commonplace book: a notebook (or digital diary) in which you catalogue quotations, lines of poetry, interesting or useful information, observations, etc., you encounter. John Locke has a handy guide.

Lingering Question

What can you cut out from your life in order to achieve greater concision?

—

I’m trying to get to my first 100 subscribers. I put a lot of time, effort, and thought into these newsletters in order to bring something meaningful & beautiful to the life of you, my beloved Reader. If you shared this with just one other person, it would help keep Soul-Making going and encourage me to create even better content for you, and I would be eternally grateful.

Thank you all so much for reading! If you enjoyed, please like this post, leave a comment to let me know your thoughts, and subscribe if you haven’t already. I hope you are all having a wonderful summer so far!

Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus.

The Iliad, or The Poem of Force (1939).

Photograph source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/25406886@N03/8467645685

"To come to an understanding of someone demands a meteorology of their internal weather patterns."

As a student of human nature, I think you've hit on the perfect metaphor Ramya!! 👏

Ramya, I feel there is nothing frivolous about your 'Friday Frivolity' :-); lots of fun to read, ponder and learn. I like your question - Aren’t emotions simply internal weather?. love your picture board and your beauty tip this week!!!. Looking forward to next week's Friday Frivolity.