Friday Frivolity no. 25: Useful Application of Literature

on literary metempsychosis and the relief of language

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a mood board, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

Useful Application of Literature

My favorite performance of Hamlet’s “What a piece of work is a man!” soliloquy comes not from any stage adaptation, not from any film version, not from Laurence Olivier in 1948 or Kenneth Branagh in 1996 or Ethan Hawke in 2000, but from a movie in which two down-on-their-luck, alcoholic, shivering actors in the late 1960s drift off to the country, where they argue with one another, avoid a gay uncle, demand booze in no uncertain terms, and menace a local café (not in that order), before speeding inebriatedly off to London, getting pulled over and arrested, returning to their flat to pass a joint among friends, and receiving a notice, after failing to pay rent, of eviction. Then Withnail and I part ways, “I,” the younger, slightly more successful of the two heading off towards a future less bleak, we presume, than the inclement weather, Withnail stuck in the dour downpour, the full force of his acting talent and skill and dreams and aspirations thrown literally to the wolves, as he recites Hamlet’s soliloquy to that lupine audience shut up behind the bars of a zoo, to the weather, to himself.

Somehow this performance in Withnail and I (1987), divorced from all context of the play, seems to more wholly inhabit Hamlet’s spirit than any performance of the play itself. This man, desolate, wasted by drink, having squandered his talents and lost his youth, drenched in the rain, talking to himself but almost with the desperate hope of being heard, out-Hamlets Hamlet. It is his own spirit that proclaims that “this majestical roof, fretted with golden fire: why, it appeareth no other thing to me, than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours,” that “Man delights not me; no, nor Woman neither.” He plays no role, he simply is the Prince of Denmark, and we see that this is the point, after all, of that singular character who is too large to be contained by his own play, whose wit eclipses everyone else’s—that his words become your words, that his words become the language of your soul and of your inmost being, that they give form and order to that rude and shapeless chaos of emotion more accurately than anything you could have thought of yourself, allowing you the relief, then, of language: yourself reflected back to yourself, whole, distinct, able to be taken between thumb and forefinger.

As of a submerged body in a pond whose breath bubbles up to the surface every now and again, the words of the poet should rise up to the surface of the mind, unbidden, yet arriving just when needed, grasping the feeling and the situation like a pinch. They should have this metempsychotic ability, able to float from one soul to the next, from one situation to another, reincarnating in many bodies. Perhaps this is the true test of the great writer: do the words come to you almost like your own thought, like inspiration or genius or memory, what you would wish to think or say were your thinking or speech raised to the highest possible level? I think of Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, in which Shakespeare’s words, “Fear no more the heat o’ the sun / Nor the furious winter’s rages” ring continually through Clarissa Dalloway’s mind and day like an incantation, carrying, yes, its original funeral context and the taint of death, but gathering also into itself “Hatchards’ shop window,” “white dawn in the country,” “the shock of Lady Bruton asking Richard to lunch without her.”

It is time now to admit that I often suspect myself of being a bad reader. Oh, I read vastly and deeply, I highlight and I take notes, I look things up I don’t know or words I don’t recognize, I write down quotations that stand out to me, I reflect and ponder and turn about characters and symbols in my hand like a pebble. But for all that my memory is a sieve; plots, except for their most basic outlines, disappear, characters’ names grow fuzzy. I think I have forgotten, that in the vast void of memory all of it has been swept away and scattered to the wind. Oh well, I muse a little sadly to myself, the momentary pleasure in the instance of reading must have been enough, it is too greedy to ask for anything more. After all, reading is a pleasure, a luxury, a gift.

Then, suddenly, at a party or on a street corner or in the throes of some desperate feeling, like a melody heard years ago—walking down a dark lane somewhere, in Rome or Reykjavik—a phrase comes, faintly at first, then more distinctly. It unravels itself like a thread. There is a flash, a revelation, a ring of the bell. You remember—you remember yourself. For you, too, are Hamlet, having of late, but wherefore you know not, lost all your mirth; you are Jane Eyre, with your morsel of bread snatched from your lips, and your drop of living water dashed from your cup; you are Clarissa Dalloway, stiffening on the kerb, waiting for Durtnall’s van to pass, and you are going to buy the flowers yourself.

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

Anne-Sophie Tschiegg, Germinations: Tschiegg is a French artist working in Strasbourg whose work uses vivid colors and textures to render portraits, landscapes, and organic forms like flowers. Here I love the mutedness of the background, which allows these green seedlings to stand forth, a fitting symbol for the New Year.

Sol LeWitt, Double Negative Pyramid (1997): This highly geometrical structure is located in a sculpture park in Lithuania, where its location at the edge of water allows its beautifully symmetrical form to be reflected, and where the water’s own reflections can dance upon the concrete. LeWitt (1928–2007), an American artist, used to create written plans for his art, which he would then hand off to assistants to actually execute. “The system is the work of art; the visual work of art is the proof of the system,” he once said in an interview.

Lorenzo Quinn, Support (2017): When I visited Venice in the summer of 2017, floating by in a water bus on the Grand Canal, I had no idea that these hands had been installed only recently for the Venice Biennale—they looked so much a part of the cityscape already, as though they had always been holding up the Ca’ Sagredo. According to Quinn, they represent the threat of rising water levels to The Floating City, serving as a physical marker of climate change, as well as a symbol of how human hands have the power to both hurt and help, destroy and repair, sink and support.

Abdur Rahman Chughtai (1894–1975), Hiraman Tota: Pakistani painter Abdur Rahman Chughtai synthesized the Mughal miniature with Art Nouveau from the West, taking inspiration from Islamic calligraphy and art traditions to render subjects from Hindu mythology and Persian folklore. This painting, probably his most famous, depicts the 13th-14th century Rajput queen Padmavati, who was known for her talking parrot Hiraman, seen here on her shoulder, camouflaging into her garment, which itself seems to blend with the lush green leaves in the background. Her legend has been told and retold in various accounts over the centuries—typically, the parrot’s role is to spread the rumor of Padmavati’s beauty to the Rajput ruler Ratan Sen, who is thus inspired to overcome great obstacles in order to win her hand in marriage.

Abdur Rahman Chughtai, Usha (First Rays of the Morning Sun), 1967 1971 advertisement for Toni’s Innocent Color, published in Cosmopolitan: Advertising doesn’t have to cheapen art—art can elevate advertising, as this modern Venus illustrates. I love the tagline: “Not since 1485 has there been color so rich, so radiant.” The copy lets you know that Toni’s special formula works with light to create “Brilliant color that lets you give Botticelli’s Venus some real competition.” What girl would say no to that?

Syndromes and a Century (2006): Directed by Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, this movie, divided into two halves, 40 years apart, concerns the lives of two young doctors, the first a female doctor working in a rural hospital, the second a male doctor working in an urban hospital. Weerasethakul was inspired by his parents, both physicians, but expanded the film’s scope to let in the stories of other characters. I love it for its exploration of memory and its deep and moving serenity.

Leg Garden at Ramoji Film City in Hyderabad, India: Ramoji Film City is a movie-themed amusement park, and I was certainly amused by these legs, as though the rest of the sculpture is stuck under the grass, enjoying the dirt. Actually, it is only a few feet away, much smaller in scale, reclining on its arms, gazing at its mammoth lower limbs in serene contemplation.

photograph by vincelaconte @ Flickr Centre for Useless Splendour: I saw this sign on Tumblr, looked it up, and it turns out the Centre for Useless Splendour is a real place, an “unofficial research hub operating within the Contemporary Art Research Centre (CARC) at Kingston University” in London. Apparently it was conceived of by Professor Elizabeth Price in order to grapple with the role of artists as researchers in a university context. Its four rooms explore the various ways in which art encounters the world: according to Dean Kenning, “the social (Foyer), the technological (Machine Room), the epistemological (Hall of Records), and the material (Lumber Room).”1 I think “Centre for Useless Splendour” is an accurate way of describing my brain, to be honest.

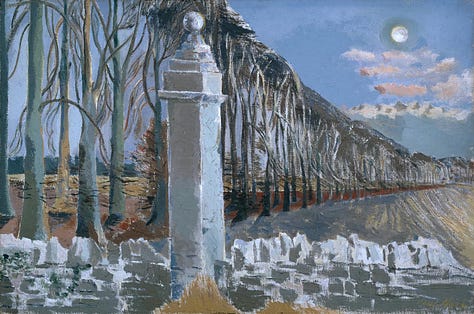

Paul Nash, London: Winter Scene, No. 2 (1940): British artist and surrealist painter Paul Nash (1889–1946) was known for his landscapes and his modernist depictions of WWI and WWII. The snowy bareness of this winter scene, with its composition of the gates in the foreground and the dark, winding tracks of cars leading mysteriously to a copse of trees in the distance, makes me hope for more snowy wintery days and seems a fitting addition to my winter post.

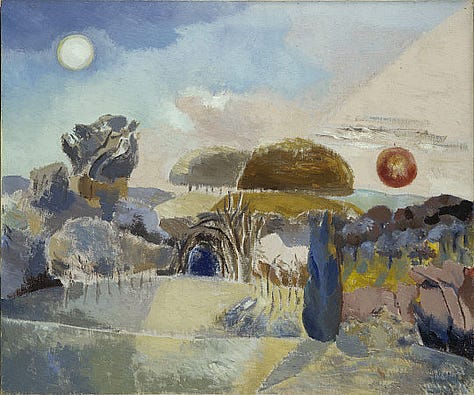

Paul Nash, Pillar and Moon (1932–1942); Landscape of the Vernal Equinox (1943); Landscape of the Moon's Last Phase (1944)

Three Things I’m in Love With This Week

3 Interesting Chairs!

Golden Gaudi Chair by Vico Magistretti from Okay Art: I love anything illuminated, manuscript-like, with gold leaf, and this chair is no different. The Gaudi Chair was designed by Italian architect and designer Vico Magistretti (1920–2006) in the 1970s, using a pressure mold of polyester resin reinforced with fiberglass in order to construct the chair as a single piece. The gold leaf brings out its gentle curves and the simplicity of its design. “Like contemporary sculpture. Enduring. Functional,” reads an ad from Bloomingdale’s, and I can’t help but agree.

Baradelo Chair by Setsuo Kitaoka, 1988: Setsuo Kitaoka (1946–) is a Japanese interior designer who established Kitaoka Design Office in 1977. He has designed stores for fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto and for Kenzo. This chair caught my eye not just because of the pink color but because of the way the seat waterfalls down to the floor, as well as how its triangular shape contrasts with the semicircle of the back/arms of the chair, yet fitting together in a way that feels harmonious and streamlined. Not very comfortable-looking, to be sure—perhaps some chairs are made to be looked at rather than sat in.

Wood Chair by Marc Newson, made by Cappellini in Milan, 1988: Marc Newson (1963–) is an Australian designer whose clients have included Hermès, Nike, and Apple, where he’s a Designer for Special Projects. This chair was commissioned for the exhibition “The House of Fiction: Domestic Blueprints in Wood” by the Crafts Council of New South Wales and is made of Canadian rock maple and Australian coachwood. As Newson had little experience working with wood up to that point, he borrowed techniques from boatbuilding, using steam in order to bend slatted strips of wood into a shape resembling the Greek letter α. I found Newson’s design philosophy interesting for the way he doesn’t make any pretensions toward artistic immortality, any grandiose statements. When asked what designers should strive for, in comparison to architects and fine artists, he replied, “The point of design for me is to provide choice, to solve problems, and to raise the bar of what is available to consumers. The best thing about design is that you can take it or leave it.”

Words of Wisdom

I feel there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people.

—Vincent Van Gogh

Someone recently intimated to me that, were all the art of the world to disappear, everything would be fine because we’d just revert to our conversation with other people. I’ve often had this suspicion myself, but I don’t know that it’s true. On the other hand, there is something about making art and feeling for one’s fellow creatures that goes hand in hand, even if the art in question doesn’t explicitly feature or have to do with people. Maybe it’s a certain warmth and empathy. After all, the best art touches the soul, and one can’t do that without a love for people.

Poetry Corner

To the Film Industry in Crisis

Not you, lean quarterlies and swarthy periodicals with your studious incursions toward the pomposity of ants, nor you, experimental theatre in which Emotive Fruition is wedding Poetic Insight perpetually, nor you, promenading Grand Opera, obvious as an ear (though you are close to my heart), but you, Motion Picture Industry, it’s you I love! In times of crisis, we must all decide again and again whom we love. And give credit where it’s due: not to my starched nurse, who taught me how to be bad and not bad rather than good (and has lately availed herself of this information), not to the Catholic Church which is at best an oversolemn introduction to cosmic entertainment, not to the American Legion, which hates everybody, but to you, glorious Silver Screen, tragic Technicolor, amorous Cinemascope, stretching Vistavision and startling Stereophonic Sound, with all your heavenly dimensions and reverberations and iconoclasms! To Richard Barthelmess as the “tol’able” boy barefoot and in pants, Jeanette MacDonald of the flaming hair and lips and long, long neck, Sue Carroll as she sits for eternity on the damaged fender of a car and smiles, Ginger Rogers with her pageboy bob like a sausage on her shuffling shoulders, peach-melba-voiced Fred Astaire of the feet, Eric von Stroheim, the seducer of mountain-climbers’ gasping spouses, the Tarzans, each and every one of you (I cannot bring myself to prefer Johnny Weissmuller to Lex Barker, I cannot!), Mae West in a furry sled, her bordello radiance and bland remarks, Rudolph Valentino of the moon, its crushing passions, and moonlike, too, the gentle Norma Shearer, Miriam Hopkins dropping her champagne glass off Joel McCrea’s yacht, and crying into the dappled sea, Clark Gable rescuing Gene Tierney from Russia and Allan Jones rescuing Kitty Carlisle from Harpo Marx, Cornel Wilde coughing blood on the piano keys while Merle Oberon berates, Marilyn Monroe in her little spike heels reeling through Niagara Falls, Joseph Cotten puzzling and Orson Welles puzzled and Dolores del Rio eating orchids for lunch and breaking mirrors, Gloria Swanson reclining, and Jean Harlow reclining and wiggling, and Alice Faye reclining and wiggling and singing, Myrna Loy being calm and wise, William Powell in his stunning urbanity, Elizabeth Taylor blossoming, yes, to you and to all you others, the great, the near-great, the featured, the extras who pass quickly and return in dreams saying your one or two lines, my love! Long may you illumine space with your marvellous appearances, delays and enunciations, and may the money of the world glitteringly cover you as you rest after a long day under the kleig lights with your faces in packs for our edifications, the way the clouds come often at night but the heavens operate on the star system. It is a divine precedent you perpetuate! Roll on, reels of celluloid, as the great earth rolls on!

—Frank O’Hara

I used to live in LA for a couple of years as a very small child, and though all I remembered from back then was the offensive and unscrupulous sun, I revised my opinion of that sprawling city a few years ago when I went to visit an old friend and experienced the beauty of its nature and neighborhoods and the Getty Museum, which I loved, thankfully spared by the horrific wildfires which have caused so much destruction. Coincidentally, somehow or another, little by little, my YouTube algorithm this week has filled up with clips of Old Hollywood stars, who have something about them that actors and actresses these days, quite frankly, can’t match up to. The wildfires made me think of American culture—lots of people say America doesn’t have culture, but I say we do, and Hollywood is so distinctively, so uniquely and wholly a part of it, so American in a way the more European East Coast (at least here in Boston) doesn’t seem to be, even if we are considered more “Cultured.” So I will leave you with this headlong, joyful, exuberant tribute of Frank O’Hara’s and hope that the smoke will clear up and leave the heavens over California to operate its star system in peace soon enough.

Beauty Tip

Try a fruit or vegetable you’ve never tried before!

Lingering Question

What kind of chair would you be if had to be a chair? I think I would be an old, perhaps overstuffed, floral-patterned rocking chair.

Dear Readers, I hope you enjoyed this one! As always, let me know your thoughts in the comments, give this post a like if you enjoyed, and subscribe to Soul-Making for more reflections on chairs and Hamlet.

"Old Hollywood stars, who have something about them that actors and actresses these days, quite frankly, can’t match up to. "

And perhaps it is also we who have changed, so longer capable of sitting in the dark and being thrilled and transported.

"we see that this is the point, after all, of that singular character who is too large to be contained by his own play, whose wit eclipses everyone else’s—that his words become your words, that his words become the language of your soul and of your inmost being, that they give form and order to that rude and shapeless chaos of emotion more accurately than anything you could have thought of yourself, allowing you the relief, then, of language: yourself reflected back to yourself, whole, distinct, able to be taken between thumb and forefinger."

Brilliant writing Ramya!! 👏