Friday Frivolity no. 24: Tell Me, Muse, About a ___ Man

Wandering through Homer's Odyssey

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a moodboard, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

Tell Me, Muse, About a ___ Man

As you set out for Ithaka hope your road is a long one, full of adventure, full of discovery.

—C. P. Cavafy, “Ithaka”

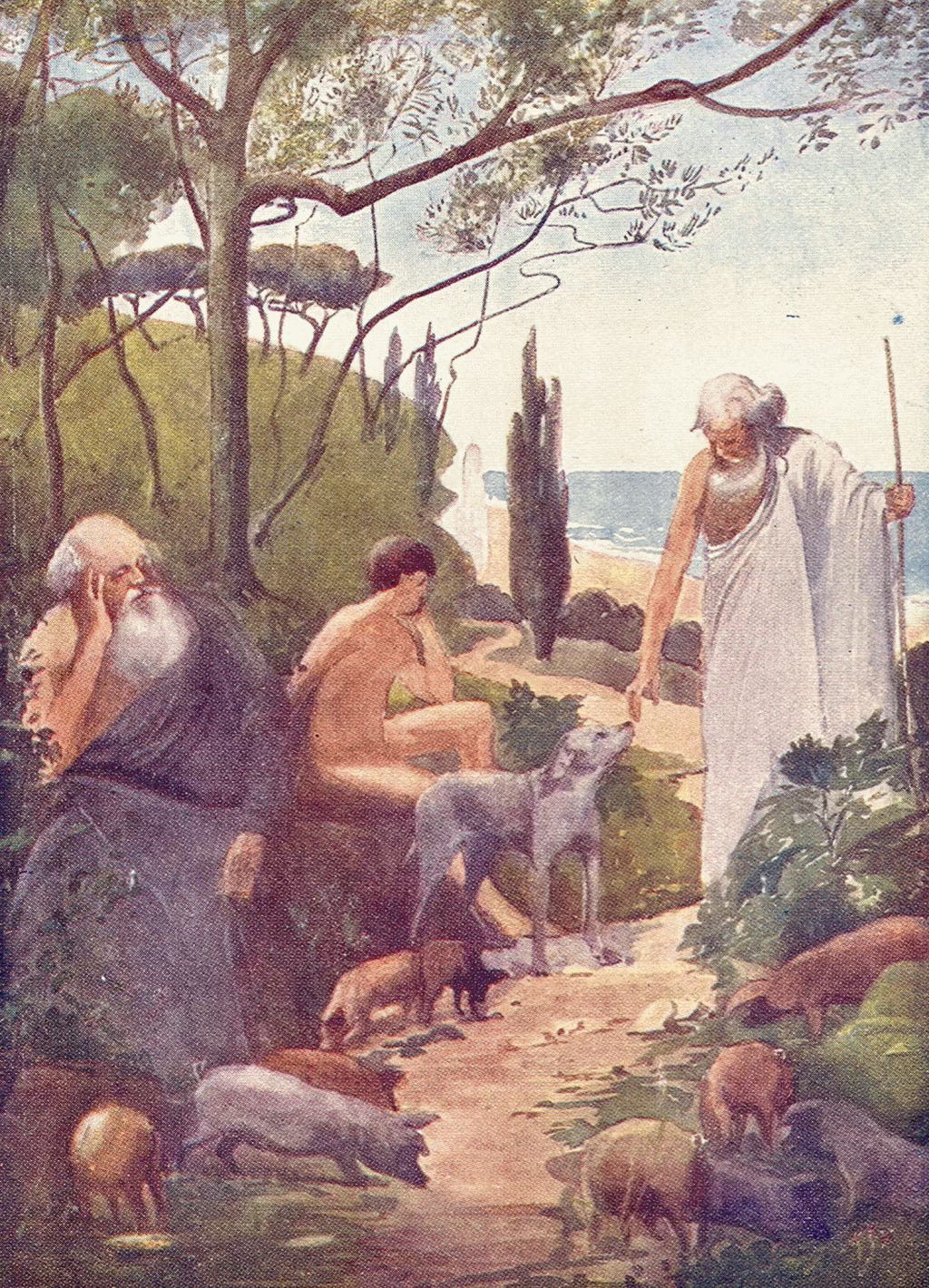

I like how the whole of an Ancient Greek epic can be encapsulated by a single Ancient Greek word. For the Iliad it is μῆνῐς (menis), “rage, wrath”; for the Odyssey it is πολύτροπος (polytropos). Polytropos is a word that is wily by nature, as wily as the man it describes, forever slipping out of our attempts to grasp it, like a fish. Literally meaning “of many turns,” from poly (“many”) and tropos (“turn, way”), it describes Homer’s epic itself, our hero’s journey back home to Ithaca after the Trojan War, as the god Poseidon harries him and his companions across the seas and to seagirt islands, into the beautiful arms of sea nymphs who promise men immortality and witches who turn men into pigs, beneath the seductive sway of Lotus-Eaters and Sirens, into encounters with winds and wind-gods, Lestrygonians and Scylla and Charybdis, into gobbling up the flock of a Cyclops and the oxen of the Sun, until, windswept and weathered by wandering, Odysseus reaches his own dear doorstep, slays the suitors eating him out of house and home, and reunites with his son, his father, his old nursemaid, his wife, and his dog, who dies instantly after an ecstatic recognition of his master.

Most stories are about “there and back again,” as in Tolkien’s The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. You start at home, safe and cozy and snug, when something impels you to leave—work, or friends, or an empty fridge, or the glimmer of true love, or an old oath you made that now binds you to fight in a decade-long war, or boredom, or wanderlust, pure and simple. Once away from home, you have your little adventure, and then you begin to hunger for home again—it was so cozy, after all, and where else can you get a warm meal and a hot bath in exactly the way you like, and all your favorite things are there, and there’s something so familiar about it, so particularly yours, and perhaps—best of all—someone waits there for you, contemplates your return, is thinking of you even now, weaving and unweaving dreams of greeting you with eager eyes and warm, open arms.

Wandering without this Ithacan promise of home would be no fun at all. You would feel cast out upon the world, alone, cold, frightened, forever in exile. Then adventure would become adversity, travel a travail. But being at home forever with nowhere and no means to wander, the customary fate of women until rather recently, is also no good. I think of Penelope, sitting there at her loom hour after hour, day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year. Wasn’t she bored? Didn’t she long for adventure of her own or to see the wide world, to know many people and many places, to “stop at Phoenician trading stations” and “to buy fine things, mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony, sensual perfume of every kind”?1

Then again, she had her tapestry, a kind of screen on which she could project any image her crafty imagination could thread together. Calypso with her powers of concealment, Circe with her spells, the Sirens with their song are all artists, as much as the male bards who strum their epics at banquets, but I think the poet finds a kindred spirit most of all in Penelope. As she weaves her mind wanders. It goes out to her husband, and then out further, to distant shores and ports, to cities and to gods, to a horizon where sea and sky blur into one, where a ship reaches the utmost boundary of the world and disappears and the sun glitters on the water, beckoning.

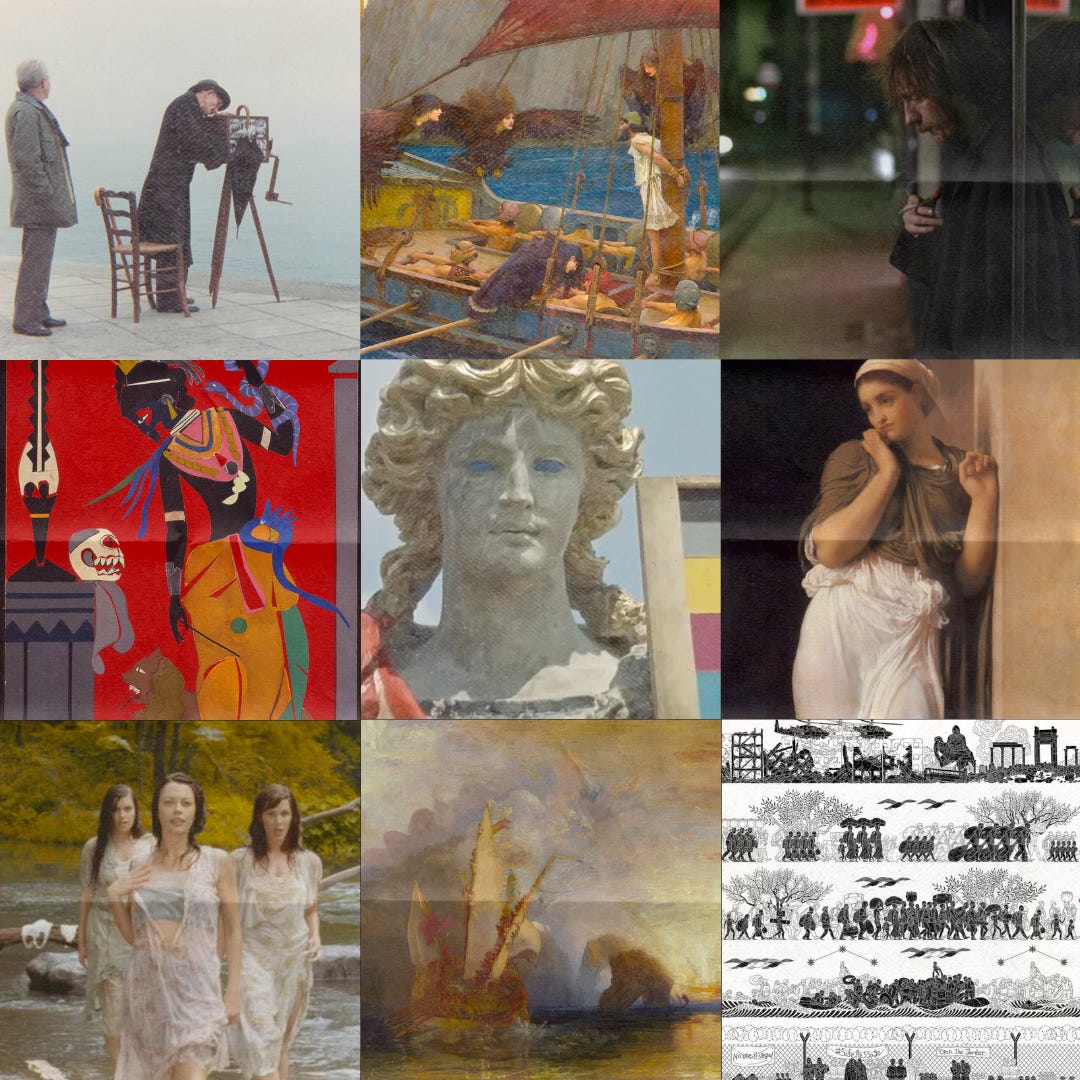

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

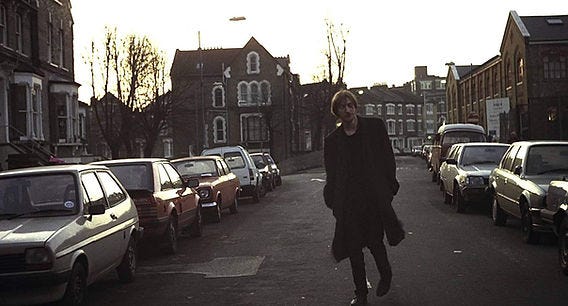

Ulysses’ Gaze (1995): Greek filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos takes his unlikely Odysseus, A (Harvey Keitel), a Greek filmmaker not unlike Angelopoulos himself, on a journey across the Balkans to find reels of film shot by the Manaki brothers, very real Balkan pioneers of cinema—these film reels might contain the first fragments of film ever shot in the Balkans, predating The Weavers (1905), which, depicting the Manakis’ 114-year-old grandmother weaving, represent a kind of Penelope for A. / In an interview, Angelopoulos admits that he didn’t like Homer much at first—required reading for Greek schoolchildren—but later came to see the epics’ outsized influence on Greek culture. In this odyssey, A journeys through various countries using various modes of transportation: a taxi, a train, a barge carrying a giant statue of Lenin, a row boat. His is a journey that mingles artistic and historical aspirations with mythology, memory, and politics. “I will tell you about the journey all the night long. And in all the nights to come. Between one embrace and the next. Between lovers’ calls. A whole human adventure. The story that never ends.”

John William Waterhouse, Ulysses and the Sirens (1891): In the Odyssey, as Odysseus’ ship sails past the Sirens, whose enchantingly beautiful song lures sailors to their watery death, he has his crew stop their ears with wax, as advised by the witch Circe. Circe tells Odysseus that if he really wants, he himself can listen to the Sirens’ song: all he has to do is have his men bind him to the mast of his ship. In this painting with Waterhouse, we see exactly that, as the Sirens—not the mermaidic creatures we might expect, but winged, bird-like figures— flock around. Waterhouse may have been inspired by this 5th-century BC Greek vase in the British museum, which paints a strikingly similar scene of a mast-bound Odysseus pelted by bird-women.

Waterhouse, Ulysses and the Sirens (1891) / Vase depicting Ulysses and the Sirens in the British Museum, 5th century BC / 3rd century AD mosaic of Ulysses and the Sirens in the Bardo National Museum Naked (1993): Mike Leigh’s film is a grungy portrait of a man, Johnny (David Thewliss), a dissatisfied and disillusioned intellectual, wandering the streets of London, who is naked of possessions and naked of identity. Like Odysseus, he tells people, “I am nobody,” and like Odysseus, is content to weave webs of ambiguity around everyone else, as though words are his only garment for sheltering his all-too-naked heart. There’s a funny scene where he goes to a girl’s place and sees a copy of the Odyssey on her bookshelf. He holds it to the camera. “Do you get it now? Do you know this? I bet you do. You’ve most likely done it at school. You just can’t remember. You know, like, uh, Achilles’ heel, the wooden horse, Helen of Troy. You know them?” “Yeah,” replies the girl. “Yeah,” says Johnny, “Well, that’s all it is. Good stuff.” Which is basically me with my Classics degree.

Naked (1993) Romare Bearden, Circe (1977): I featured the 20th-century American artist and collagist Romare Bearden in my post on the Iliad. About 30 years after his drawings and watercolors of the Iliad, he visited the Odyssey in the 1970s, creating a series of 20 collages that draw on African art and contemporary African-American culture, inviting viewers to inhabit Homer’s epic in a way that is fresh, vivid, dynamic, colorful, and exhilarating.

Contempt (1963): Contempt (Le Mépris), directed by Jean-Luc Godard, is one of my favorite movies, and one that I’ve written a little bit about here. Godard loves meta-commentary on cinema itself, and here it takes the form of a film-within-a-film directed by legendary director Fritz Lang (starring as himself), who is adapting Homer’s Odyssey for the big screen. Lang must contend with brash American producer Jerry Prokosch, who hires Paul, a young French playwright, to work on the script. Paul is the Odysseus to Brigitte Bardot’s Penelope, Camille, who grows ever more scornful of her husband for reasons that remain obscure to him (though, I suspect, have to do with his “selling out”). Contempt is a film about translation and its failures: failure to translate ancient epic into modern cinema, failure to translate artistic visions between a French man, an American man, and a German man, in spite of the assistance of an Italian woman, and failure to translate feelings into words, love into something lasting and true and real. Nevertheless, it may be enough that, once in a while, something passes the barrier, something communicates, something, however violently, is understood, which is what we call “art.”

Frederic Leighton, Nausicaa (1878): Odysseus encounters Nausicaa, a young princess, when he is shipwrecked on the island of Scheria. She and her handmaidens have gone to wash clothes and begin playing their innocent, girlish games, when Odysseus emerges naked from the underbrush, scaring the handmaidens. Nausicaa, however, takes a liking to the hero, giving him clothes and olive oil. Odysseus bathes in a stream, anoints and dresses himself, and with a little help from Athena is made to look just a smidge handsomer, such that Nausicaa tells her friends, “Would that such a man as he might be called my husband.”2 I love the simple and sweet way Leighton depicts her here, her garments not ostentatious or princess-y but becoming of her youth, a wistful, faraway look in her eyes that reminds me of Gertie MacDowell, Joyce’s Nausicaa analogue in Ulysses, who spends half a chapter dreaming of romance.

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000): Joel and Ethan Coen set their Odyssey in Mississippi in 1937, following three convicts who escape a chain gang to go on a serious of misadventures through cotton fields, freight trains, and KKK rallies. Come for young George Clooney, stay for the folk music you can’t help but tap your foot to.

J. M. W. Turner, Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus (1829): Odysseus and his shipmates, tossed and turned on the sea while sailing home from the Trojan War, find themselves on a small island. Hungry and hearing the bleating of goats from a nearby, larger island, Odysseus selects his 12 bravest companions and comes to the cave of Polyphemus. The giant, one-eyed shepherd is absent, and Odysseus and his men, finding vast quantities of cheese, begin to eat. Unfortunately, Polyphemus comes home, discovers them, and makes a supper out of four of Odysseus’ men. He sleeps and in the morning goes off to graze his flocks, leaving Odysseus time to come up with a plan. He sharpens an olive-wood cudgel, gets the Cyclops drunk on wine from his ship, and when Polyphemus asks him for his name, tells him it is “Nobody.” When Polyphemus is fast asleep at last, Odysseus and his men ram the cudgel into his one eye. Polyphemus cries out in pain, asking his fellow Cyclopes for help, but they laugh at him when he tells them he has been attacked by “Nobody.” Odysseus and his men escape, hanging upside down under the belly of sheep, and when Odysseus is safe on his ship again, he taunts the Cyclops, who throws a rock at him. Odysseus, in spite of his men’s reproaches, can’t help but taunt Polyphemus yet again, finally giving him his name: “say that the one who blinded you was Odysseus the city-sacker.”3 Polyphemus groans and says that this had been prophesied to him; he invokes his father, Poseidon, to make sure that Odysseus does not come home, or if he does, it is only after much misery, and only to find mischief reigning in his home.

details from Turner's Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus (1829) Here, Turner’s seascape turns the Cyclops into the “shaggy peak in a mountain-range” he resembles. I love the water spirits at the foot of the ship, as well as the vague forms of horses pulling the chariot of the rising sun.

Ai Weiwei, Odyssey (2017): That war creates exiles is something that has not changed between Homer’s time and ours. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei (1957-) took inspiration from his own project, Human Flow (2017), a documentary on the refugee crisis for which he traveled to 40 refugee camps, as well as the style of Ancient Greek pottery, in order to create this epic frieze, where modern tanks lurks among ancient ruins.

3 Things I’m in Love With This Week

Omeros by Derek Walcott: Derek Walcott (1930-2017) transformed the Odyssey into his own epic poem, relocating it to his own island of St. Lucia. His protagonist Achille’s journey is a kind of katabasis, a journey to the underworld that echoes Odysseus’s own, as it takes him through his ancestors’ and the Caribbean’s past of slavery and colonialism, jumping between the Caribbean, Africa, Europe, and the U.S. “All of the Antilles, every island, is an effort of memory; every mind, every racial biography culminating in amnesia and fog” says Walcott in his Nobel Lecture. “Pieces of sunlight through the fog and sudden rainbows, arcs-en-ciel. That is the effort, the labour of the Antillean imagination, rebuilding its gods from bamboo frames, phrase by phrase.” Walcott’s “labour of the Antillean imagination” is an epic one, and beautiful.

The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel by Nikos Kazantzakis: Greek poet Nikos Kazantzakis (1883-1957) picks up where Homer leaves off, chronicling the adventures of Odysseus after he returns home, terrorizes everyone with his changed, warlike nature, and sets sail again. Like Homer’s Odyssey, Kazantzakis’ epic sequel is divided into 24 parts, consisting of 33,333 lines total. Odysseus’ journey is equally a spiritual one, underlaid by a harsh, Nietzschean philosophy that takes our hero some very strange places and links him up with some very strange figures: Helen of Sparta and stand-ins for Buddha, Don Quixote, and Jesus are encountered as he travels from Ithaca to Crete to Egypt to the ends of the earth—to Antarctica itself.

The story of Acis, Galatea, and Polyphemus in Book XIII of Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Galatea is a sea nymph who recounts her troubles in love to Scylla, of Scylla and Charybdis fame. The nymph explains that she was in love with a mortal, Acis, but was endlessly pursued by the Cyclops Polyphemus, whom Odysseus famously tricked in Book IX of the Odyssey. Seeing Galatea, Polyphemus finally feels quid sit amor, what love is. He begins to comb his “bristling hair with a rake,” he cuts his “shaggy beard with a reaping hook,” he looks at his ferocious expression in the mirror of a lake and tries to recompose it into something friendlier. His bloodthirst wanes, ships can now pass safely at last. A seer comes to him and tells him that Odysseus will take his single eye from him. The Cyclops laughs off the warning—“O, most foolish of seers, you are wrong, another, a girl, has already taken it.” Then, with a panpipe made of a hundred reeds, he begins to serenade Galatea in flowery language: “Galatea, whiter than the snowy privet petals, / taller than slim alder, more flowery than the meadows, / friskier than a tender kid, more radiant than crystal….”4 He tries to impress her with the size of his flock, he promises her twin bear cubs to play with, he defends his hirsuteness and his one eye, he pledges Neptune as a father-in-law. Polyphemus the lover is hilarious—and hopeless.

Words of Wisdom

Think you’re escaping and run into yourself. Longest way round is the shortest way home.

—James Joyce, Ulysses

In Ulysses, Joyce took the journey of Odysseus and brought it into 20th-century Dublin, making his modern Odysseus the wonderful everyman Leopold Bloom, a Jewish adman who wanders about town over the course of a single day, June 16, 1904. His old hero Stephen Dedalus stars as Telemachus, Odysseus’s son in search of a father, while Bloom’s wife, Molly, plays Penelope, a very earthy, sexual Penelope who lacks much of the cunning—and the faithfulness—of Homer’s original.

Joyce was first introduced to the Odyssey as a child through Charles Lamb’s The Adventures of Ulysses, a shortened retelling of the epic intended for children. Atop the Odyssey framework, Joyce layers Shakespeare, Dante, Christianity, Irish politics and history, medieval philosophers like St. Thomas Aquinas, references to contemporary culture, and much, much more. In Frank Budgen’s recollections of his conversations with Joyce about the writing of Ulysses, he asked him one day how the book was going:5

I enquired about Ulysses. Was it progressing?

“I have been working hard on it all day,” said Joyce.

“Does that mean that you have written a great deal?” I said.

“Two sentences,” said Joyce.

Indeed, the polytropic nature of the book has for over a hundred years sent scholars on their own odysseys through Joyce’s text. But approach Ulysses as a novel, not as a code to crack of hieroglyphics to decipher, and you will find that it is not only immensely rewarding but also great fun. Journeying through these seas and islands and streets of words, we find that we “run into [ourselves],” and we are all the better for it.

Poetry Corner

Come, my friends, ’Tis not too late to seek a newer world. Push off, and sitting well in order smite The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of all the western stars, until I die. It may be that the gulfs will wash us down: It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’ We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are; One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

—from “Ulysses” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

In “Ulysses,” Tennyson has Homer’s hero speak to us many years after his homecoming. He is an old man now, “[m]atch’d with an aged wife,” and, contrary to what we might think after reading Homer’s epic, that Odysseus would have been glad, after ten years of war and another ten of wandering, to finally come back to the comforts of home and hearth, wife and son and native land, he hungers for adventure, misses it, feels unsatisfied in his role as “idle king” who “mete[s] and dole[s] / Unequal laws unto a savage race.” Like Dante’s Ulysses in the Inferno, whose “desire… to be experienced of the world”6 cannot be overcome by his affection for his loved ones, Tennyson’s Ulysses is not drawn by the force of home but is impelled by the greater power of new experience, knowledge, “To follow knowledge like a sinking star, / Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.”

This is an Odysseus who has traveled through many lands and met many peoples and now feels stultified by his narrow life at home in Ithaca. Boredom and ennui have set in. Tennyson wrote “Ulysses” after the death of his friend Arthur Henry Hallam, who also inspired his sustained elegy In Memoriam AHH; Hallam and Tennyson met as students at Cambridge and became very close, traveling the continent together, Hallam becoming engaged to Tennyson’s sister. “Ulysses” reflects some of that meaninglessness we find in life in the wake of grief, that feeling of missing something, looking for something. Tennyson’s Ulysses is a man who is searching for something without knowing quite what he’s searching for. He acknowledges that, in his eternal quest, the goalpost is always moving—“all experience is an arch wherethro’ / Gleams that untravell’d world whose margin fades / For ever and forever when I move.” Yet he prefers it this way, for seeking, exploring, wandering, odysseying mean life itself.

Beauty Tip

Set out on a mini-odyssey. Leave your home and take a walk or a car ride without any particular destination in mind, just wandering where your curiosity leads you. Then head back when you start to long for home again.

Lingering Question

What is one of the most unexpected places life’s journey has taken you, and how did that shape you as a person?

Dear Readers, there’s been so much discourse lately about the Odyssey after Christopher Nolan announced that he would adapt Homer’s epic into a film and then people started hating on Emily Wilson’s translation (which I think is great!). I’ve been wanting to write a follow-up to my Iliad post for a while, so it was as good an opportunity as any.

I hope you enjoyed—please like this post if you did, subscribe to Soul-Making to get more posts like this every Friday, plus additional essays, poems, etc., and let me know your thoughts in the comments!

C. P. Cavafy, “Ithaka.”

From the translation by A. T. Murray.

From the translation by A. T. Murray.

From the translation by A. S. Kline.

Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses, 1934.

Dante, Canto XXVI of the Inferno, translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Fabulous essay Ramya! 👏 Rich and deep and expertly referenced. Will restack.

Your reference to the "there and back again" structure of Homer's and Tolkien's masterpieces of course conjures up Joseph Campbell's analysis of the "hero's journey" motif in so many dramatic works:

"The hero’s journey always begins with the call. One way or another, a guide must come to say, ‘Look, you’re in Sleepy Land. Wake. Come on a trip. There is a whole aspect of your consciousness, your being, that’s not been touched. So you’re at home here? Well, there’s not enough of you there.’ And so it starts."

“Most stories are about “there and back again,”- I agree and invariably it is the people whom we care for, love, admire, most of all we miss that draws one to come back to. Very nice poetic writing.

I have been following your writing for quite some time and always admire how versatile your writings and topics are. It connects human experiences with society, weaves it in the context of history , mythology and provoked the reader to think. Great work Ramya! Looking forward to your next week.