Friday Frivolity no. 22: Bleak Beauty

An ode to winter and to all things wintery

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a moodboard, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

Bleak Beauty

Last night I was looking at old photographs of my father as I often do these dark winter nights. Soon after he had passed, I scanned all of my parents’ old film photographs and saved them in my computer. Upon this latest perusal, there were three photos that stood out to me in particular, all of them of my father in the winter. My parents had come to Boston in the late ’80s, and these pictures, taken in the ’80s and ’90s, evoke a certain nostalgia. In all of them, my father has a mustache, a facial accessory he got rid of soon after I was born, and a gray hat I’ve never seen in the flesh. There is the vintage film grain, the old cars, something ghostly about the light that sharpens a web of winter branches. But the most nostalgic thing about these photographs is the amount of snow: enough snow for footprints to be trodden into, effaced, and trodden into again, enough snow that one has to carve a path for oneself in it, snow that one’s foot and ankle would surely sink into, enough snow to make a signpost barely visible and weigh down innumerable branches, forcing them to bend and stoop and groan with their cold burden, snow to blind and blanket the world, to make it a blank thing, so many inches and feet and miles of snow, soft as fine lambswool.

If snow evokes this nostalgia for me, it is because winter, at least here in New England, is not what it once was. It has lost vim and vigor; its force has thawed. We used to have real nor’easters when I was a child, snowfall—in November, certainly by December—was typical, expected, nothing to be questioned, and my father and I would sled regularly every winter, donning our snowpants. Now the snowpants sit useless in the closet, and Christmas is inevitably “green,” i.e. dull gray, and the most one can hope for is a bit of rain that falls insipidly, depressingly, unsure of itself, that it really belongs here in this interval between its two proper haunts, fall and spring.

Is snow to become a period piece? Will it be a mark of bygone eras and times past, as sure as typewriters, bell-bottoms, and transistor radios? Will it be nothing more than a mere curiosity to future generations—“Look, that’s snow, how funny, people used to have to live with that back then”? Will having to shovel one’s driveway and salt the roads become an amusing detail of an ended epoch, as one hears of Ancient Romans washing their clothing in urine?

Winter has so many haters and detractors that, when I make observations on its gradual disappearance to friends, they seem either unbothered or actually happy. Everyone wants to be a summer hot girl, a spring fling queen, or a cozy autumnal grandma. But what about the quiet winter girls, the frost fairies, the icicle princesses, the blustery blizzard boys? Even those who claim to love winter often turn out to be fake winter-lovers: what they really love is Christmas and the holiday season, and when the presents have been unwrapped and the red and green goes away and the lights are put back into their boxes again, they sink into January blues and do not, after all, relish the cold.

Maybe I’m biased because I was born in the middle of a blizzard. Indeed, when I think of my “identity,” I see myself as neither Indian nor American but a simple New Englander. In fact, I am literally allergic to hot temperatures and dry climates; the last time I went to India, I developed heat rash. So maybe that’s why, last night, after seeing those pictures of my dad, I made a little prayer as I nodded off to sleep: Boreas, North Wind, come back from the Bahamas or California or wherever it is you are vacationing and blow your chill breath upon us again—you have a job to do, or have you forgotten?

He must have heard my calls, because when I woke up this morning and opened the blinds, I saw that—contravening the forecast earlier in the week—it was snowing, that half the yard had disappeared under a patchwork erasure, that the branches and the evergreens were edged with white. The snow was sticking, too; by midday it had acquired, like a boy going through puberty, inches and girth. It feathered the trunks of trees and the last stubborn autumn leaves. Everything held that fresh magical miraculous feeling of snowfall. Nobody was out on the road; everything was silent and hushed, as though the world slept.

I decided to go for a walk. Though nobody had shoveled yet, I had enough faith in my sturdy winter boots to brave the hills and dips without slipping. I felt warm and cozy in my winter coat, bundled up against the chilly air. The cold nipped at my ungloved fingertips, but there was something satisfying in that cold burning, something alive. The fairy-flecks fell on my face like cool kisses. I had taken my film camera with me; perhaps, in a few decades, the snowy photographs I took would be looked at by my children or grandchildren, as I had looked at my father’s. Hopefully, by then, winter will not have turned into a curiosity.

But if I am still alive, and winter no longer exists, I will take my old self to Antarctica, armed with Bernadette Mayer’s poem “The Way to Keep Going in Antarctica.” I will live out the last years of my existence on an ice floe, drifting in an ice-cold sea, and surrender myself entirely to the cold.

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

Edward Willis Redfield, Woodland Brook (ca. 1914): Edward Willis Redfield (1869–1965) was an American landscape painter who actually specialized in winter landscapes. He worked in a largely Impressionist style, and the mood he evokes in his winter paintings is one of quiet contemplation, solitude, and stillness, reminding me of “the woods and frozen lake / The darkest evening of the year” of Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” Looking at them, one feels that winter, in its austere simplicity, needs no colors or flowers or dazzling sunlight—that the snow has not melted and the trees are not bare, that the air is gray and the light subdued, is as it should be.

Edward Willis Redfield, New Hope (1926) and The Mill in Winter (1921) Metropolitan (1990) theatrical poster illustration by Pierre Le Tan: Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan is an underrated classic, my favorite Christmas movie, and basically Gossip Girl in a top hat and monocle. Stillman, a Jane Austen enthusiast, takes inspiration from that sly portraitist of social manners and mores, to chronicle the debutante season of young Upper East Siders and the one (1) representative of the middle-class they allow, temporarily, into their clan. It’s a talking movie, and a hilarious one, where discussions of Fourier and Veblen are gently teased apart to ironize their speakers’ often endearing flaws.

Buffalo ’66 (1998): Any romance that starts with a kidnapping and a forced playacting of husband-and-wife in front of one’s parents is sure to be a success. Or maybe it only works when that husband and wife are played by a surly Vincent Gallo and a delightfully charming, tap-dancing, blue-eyeshadowed, vulnerable Christina Ricci. My soft spot for unconventional romances aside, I love the dreamlike warmth with which a cold upstate New York winter is depicted, the barren trees and sunless skies and drab snow-streaked grass, along with the hometown haunts—bowling alleys and worn-down motels—that offer its escape. Also, Shakespeare was wrong. The food of love is not music. It is, as Vincent Gallo’s character finds out, a large hot chocolate and a heart cookie.

Buffalo '66 (1998) Peter Brook, JANUARY Pennine Valley (1976–7): Peter Brook (1927–2009) was an English painter known for his rural landscapes, and he often painted the Pennines, a “spine” of uplands running through Northern England. From 1976 to 1977, he made a series of lithographs, The Months of the Year, that capture the changing of the seasons. I like the flatness and starkness of his work, especially his winter landscapes—they seem so similar to the Pieter Bruegel landscape here that Brook could have been Bruegel’s contemporary.

John Galliano Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear runway show: Designing the Fall 2009 collection for his own brand, John Galliano took inspiration from Russian folklore and fairytales. On the runway, a magical Northern Lights-colored tunnel, snow falling softly within it, brings to life furs, veils, and filmy silks, all given the final fairytale touch with ornate silver jewelry and Pat McGrath’s frosty, snow queen makeup.

John Galliano Fall 2009 Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Hunters in the Snow (1565): Probably the most famous winter painting of all winter paintings, The Hunters in the Snow evokes the somberness of the season in its limited palette of gray-blue, gray-white, reddish-brown, and black, and yet it is a winter that teems with activity: the hunters returned with their spoils (not much, just a small fox), their pack of dogs behind them, surveying a scene of ice-skaters, sledders, stick-carriers, and hockey-players, as a crow wheels overhead and figures stoke a fire. At dimensions of about 4 x 5 ft, it is well worth taking the time to contemplate in detail.

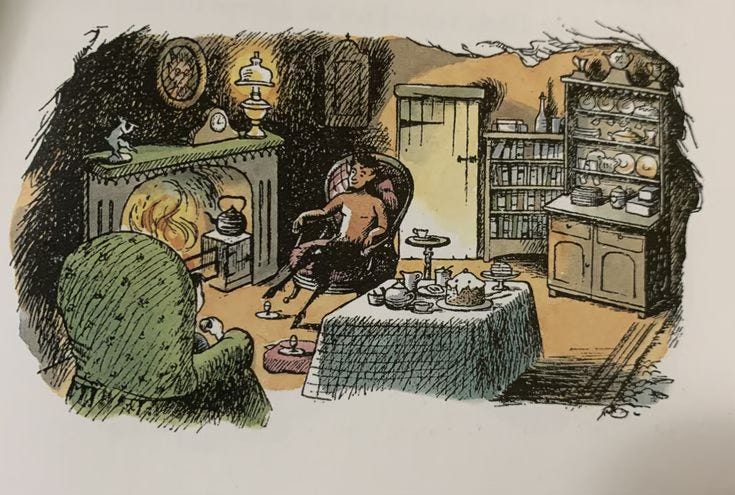

details from The Hunters in the Snow Lucy and Mr. Tumnus from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, illustrated by Pauline Baynes: The Chronicles of Narnia were some of my favorite books as a child, and I always loved Lucy Pevensie’s friendship with Mr. Tumnus, the first character she meets upon entering Narnia. Indeed, C. S. Lewis himself said that the very first spark of inspiration for the series was the image of a faun in a snowy wood, holding an umbrella, a parcel tucked under his arm, just as we first encounter Tumnus in the wardrobe. Narnia, as you may remember, is trapped in an eternal winter without Christmas. What could make eternal winter cozier than tea with a faun? And what could be a more charming accompaniment to Lewis’s tales of fauns and girls, wardrobes and witches than Pauline Baynes’s lovely, lively illustrations?

Caspar David Friedrich, The Sea of Ice (1823-4): Caspar David Friedrich, that bastion of German Romanticism, often used landscapes to convey emotional and spiritual meanings—they were mindscapes or moodscapes, showing nature as alive and forceful and teeming with feeling. Here the harsh, jagged shapes of ice jut out violently, radically into the middle of the frame, overshadowing, to the right, a poor shipwreck, nearly eaten up by ice. Friedrich was inspired by William Edward Parry’s 1819-20 expedition to the North Pole, and his studies of ice floes on the river Elbe well prepared him for this massive undertaking of nature’s wintery sublimity.

Marketa Lazarová (1967): If there is one winter movie to beat all winter movies, it is surely the Czech masterpiece Marketa Lazarová, directed by František Vláčil, based on the novel by Vladislav Vančura. It is a movie you may have to watch twice to grasp—clear unfolding of plot is shunted for other virtues: dreamlike cinematography, emotional heightening, psychological realism, a sense of the violent struggle between pagan and Christian, an enveloping, immersive recreation of the 13th century. Here winter is not the cozy backdrop for tinseled Christmases and candlelit evenings, it is a harsh, unforgiving winter, bitter in its barrenness, a winter of hard, glittering frosts, endless, unmelting snow, bleak, black trees, bloodthirsty wolves, the struggle for survival laid bare, and yet it is beautiful, a haunting, austere beauty heightened by Zdenek Liška’s soundtrack of ethereal plainchant and ghostly marimba.

Marketa Lazarova (1967)

3 Things I’m in Love With This Week

“Winter” by Jamie Scott: Five years of shooting across New York State and Montreal, Canada are condensed into three and a half beautiful minutes in which time lapses of winter are set to a mesmerizing, whirling score by composer Jim Perkins. We see frost feathering over a fall leaf, bleaching it of color, drops of water hardening into icicles, preserving branches in a cold resin, streams slowing down to an icy sludge, evergreen branches drooping with the weight of snow, snow filling up the spaces between stones and blades of grass, blanketing landscapes in white: so much power in one singular, tiny, never-to-be-repeated crystal of ice.

“Ice Huts” and “Ice Villages” by Richard Johnson: Between 2007 and 2019, photographer Richard Johnson, who passed away in 2021, documented the thousands of hand-built structures that converge around lakes in Canada in December and January, when people come in droves to ice fish. Mark Kingwell calls the ice huts “portraits of [their] owners,” and indeed these tiny dwellings are astounding in their diversity: some metal, some wooden; some carefully crafted, some cobbled together; some neon-yellow, some so colorless they blend into the winter landscape; all worth looking at and lingering over.

“Der Leiermann” from Schubert’s Winterreise: Austrian composer Franz Schubert wrote his song cycle Winterreise (Winter Journey) in 1827, setting 24 poems by Wilhelm Müller to music. In the poem cycle, Müller draws on the Romantic trope of the lone wanderer, driven by failure in love to seek self-knowledge. In the last, “Der Leiermann” (“The Hurdy-Gurdy Player”), the speaker encounters an old man, a village hurdy-gurdy player, with fingers too numb from the cold to even really play his instrument and whom no one pays the slightest attention. But the speaker notices him, and asks him, “Shall I go with you? Will you turn your hurdy-gurdy to my songs?”1

Words of Wisdom

It is said that life is inhospitable to those who reject it.

—Vladislav Vančura, Marketa Lazarová (translated by Carleton Bulkin)

After watching Marketa Lazarová, I was so tempted to read the book, and, given how experimental the movie is in terms of its storytelling and structure, I was surprised to see how much actually matched up between the book and the movie. Like the movie, but in a different way, the book feels original and revelatory, even nearly a century after its publication, with its medieval setting and the almost romantic, fairytale-esque voice of its narrator, who frequently breaks the fourth wall, sometimes in very funny ways. Carleton Bulkin’s translation is engagingly readable, and I highly recommend it if you’re looking for a good book to curl up with on a cold winter night.

Poetry Corner

I can wring out a true song about myself, tell of my journeys, how I in days of toil often suffered times of hardship, have endured bitter breast-care, tried out in a ship’s keel many dwellings of sorrow, the terrible roiling of waves. There the oppressive night-watch often seized me at the prow of the ship when it dashes along cliffs. Pinched by cold were my feet, fettered by frost with cold chains, where the cares sighed hot around my heart. Hunger within rent the mind of the sea-weary one. That man doesn’t know— he for whom it goes so prosperously on land— how I, wretched, on the ice-cold sea inhabited winter in the paths of exile, bereft of kinsfolk, be-hung with icicles; hail flew in showers. There I heard nothing but the resounding sea, the ice-cold wave. At times a swan’s song I took for my entertainment, the gannet’s cry, and the sound of the curlew for the laughter of men, a seagull singing for mead-drinking. There, storms beat the rocky cliff, where the tern answered them, icy-feathered. Very often the eagle cried at it, wet-feathered. No protecting kinsman can comfort a desolate spirit. Therefore he little believes—he who has experienced the pleasure of life in cities, proud and merry with wine—how I am weary often. On the ocean-path, I had to remain. The night-shadow darkened, it snowed from the north, frost bound the earth, hail fell on the ground, coldest of grains.

—from “The Seafarer,” Old English poem, my translation

There are so many beautiful winter poems scattered across the wide arc of literature, but my mind always goes to the first part of “The Seafarer,” which survives in the 10th-century Exeter Book. In the book, the titular seafarer describes his bitter hardships on the sea, where he endures the “cold chains” of frost and is rent by the pangs of hunger. Worse are the psychological toils, the “bitter breast-care” (literally bitre breostceare) of living apart from one’s kinsmen. The seafarer only knows the “dwellings of sorrow” (cearselda) that are the tossing and turning of waves—the ironic use of cearselda, from seld, a word typically used for sturdy dwellings on dry land, underscores the difference. Twice the seafarer notes the vast disparity between himself and the man prosperous on land, the man “who has experienced / the pleasure of life in cities” and does not have to take the calls of birds as poor substitutes for laughter, socializing, and merry-making.

However, as the poem continues onwards from here, the speaker asserts the adventure and derring-do of seafaring, the power of his own wanderlust, that longing which impels him to undertake these difficult journeys and brave far-off stretches of sea. Seafaring becomes a metaphor for the human condition itself: landlubbers as we might be, we can all say, as in the Carmina Burana, “Feror ego veluti / sine nauta navis,” “I am carried along like / a ship without a sailor” by the winds of fate. Nevertheless, the seafarer muses, there are still things we can strive for before we meet our end, and there are things (money, etc.) that pale before the direness of death and the splendor of God. The last section of the poem becomes almost self-helpy in tone, the speaker turning from descriptive to didactic to devotional, and yet it always moves me. You can read the full poem, side-by-side with the original Old English, here, and hear a bit of what the Old English sounded like, along with a deeper analysis, here.

If you’d like more Old English poetry, I translated a fun riddle in this post about a month ago:

Beauty Tip

Reach out to somebody who might be feeling a bit lonely this holiday season—you never know what it might mean to them.

Lingering Question

What can you get rid of—a habit, an object, a piece of clothing, a nonconstructive thought—before the year ends?

Hi all, I hope you enjoyed this one! If you did, please like this post and share with a friend, and I’d love you hear your thoughts on all things winter in the comments! What’s winter like in your part of the world?

Also, here’s a post I wrote on snow almost a year ago that means a lot to me now that my father is gone. I guess you can tell I have something of an obsession with snow:

From the translation here: https://oxfordsong.org/song/der-leiermann-2

Thanks for such a long and lovely meditation on the joys of winter Ramya! 👏 As a native Bostonian now living in southern CA, I remember many perfect snowy days with great fondness while embracing the warm sunny winter days here in the southwest corner.

Ramya, I think even Winter itself would feel it's heart warmed by the sheer beauty of your writing.

And I must admit, I've always been one for walking out in the bleak beauty of it all too - though we have not have much snow here either for the last couple of years.

Also, great choice with some of those artworks.

Although it did make me wonder whether the photos from your own snow walk were closer in view to Friedrich, Monet, or Brueghel's winter landscapes!