Friday Frivolity no. 17: The Iliad, Blood Poem

Homer's (anti-)war epic and its many manifestations

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a moodboard, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

So sorry this is so late!!! That’s what I get for naming a section after a day of the week. But I hope you all enjoy <3

—

The Iliad, Blood Poem

The Iliad is a red poem. From the moment Homer begins, “Wrath—sing it, goddess,” blood drips down the first syllable of the word mēnin, from mēnis, “wrath, rage, fury, anger, ire” and begins its steady trickle down the roughly 112,000 words (in Greek) of the poem, gathering in great streams here, pooling out of the mortal bodies of beautiful young men there, reaching a boiling point in the hearts of heroes bent on vengeance or glory, spreading itself outwards to stain cities, old men, young women, children, innocents, finally stopping with the last syllable of the word hippodámoio, from hippódamos, “tamer of horses,” epithet of Hector. But we know that the funeral rites of this Trojan prince, whose body was dragged in the dust around the walls of his native city by the greatest of Greek warriors, then begged for so piteously at the knees of that warrior by the father to whom it was beloved, is only a temporary staunching of blood, only a momentary pause in a great unquenchable tide. Ruin will come, the toppling of citadels, the displacement, separation, breaking up, or total destruction of families, the lamentation of women, who rend their hair and beat the earth, not only for their wretched husbands and sons but for their own wretched selves, to be stolen into slavery and concubinage for those beloved husbands’ and sons’ killers. Thus blood, once shed, overflows itself, and the air is heavy with its scent.

According to the mathematics of blood, one loss must be recompensed by another loss, the killer killed, the killer’s killer killed, and so on to infinity. What can recompense the loss of a beloved friend or lover, brother or son? What can pull a spear out of a heart, make whole the flesh again, scoop up the spilled blood, remold like wet clay bodies crumpled into dust? What can re-right these dominoes, given the first push by the love of a forbidden couple, or the abduction of a man’s wife, or another man’s desire for power and expansion, or the jealousy between three goddesses, or an apple rolled across the feast table of a wedding? Even a god cannot do it. War vanishes humans, cultures, cities, civilizations; what is done cannot be undone. Even you, sitting there, can you take back the words you have spoken in anger? Never mind what you meant, the spear has gone into the heart, and even if the flesh heals and seals, the scar remains.

If rage is the subject of epic, grief is its inevitable result in tragedy. In Euripides’ tragedy Hecuba, there is a moment when the chorus of captive Trojan women remember vividly the sack of Troy, seeing it unwind in their mind’s eye frame by frame: midnight, the songs and dances of the feast finished, the husband asleep in bed, his spear hanging on the wall,1

“I was setting my hair in the soft folds of the net, gazing at the endless light deep in the golden mirror, preparing myself for bed, when tumult broke the air…. [...] I left the bed of love, and prayed to Artemis. But the answer was, ‘No.’ I saw my husband lying dead, and they took me away to the sea. Backward I looked at Troy, as the ship sped on and Ilium slipped away, and I was dumb with grief.”

But grief is not entirely absent in the Iliad itself; it follows wrath like a shadow. Homer—whoever and however many he was—takes care to show you not only the bloodshed but also the tears shed, by parents and spouses and siblings and friends. Achilles has no respite from his wrath, no restitution for the loss of his beloved Patroclus, until he looks his grief face-to-face at last—or rather, grief comes to look him in the face. King Priam comes, shorn of his children and his city and his glory, and asks not for his son’s life again, not for the killing of his son’s killer, not for money or spoils or payment, but only for his son’s corpse, so it can be given its last and proper rites. He implores Achilles to see in him the face of his own father:2

“…pity me, remembering your father, Peleus. I am more pitiable than him. I have endured what no man yet on earth has done— I pressed my mouth into the hand of him who killed my son.”

Achilles remembers his father, the father he loves, the father whose life, too, is not devoid of suffering, whose son is alive but far away over the sea, unable to care for him in his old age, and both men, Priam remembering his son Hector, Achilles remembering his father and Patroclus, weep together, and “[s]o their wailing / suffused the house.” Achilles not only gives back the corpse but has it washed and oiled, dressed and wrapped, set on a bier and raised onto a “polished wagon,” and invites the father, famished from grief, to eat.3

If there is anything to keep Achilles’ name alive in the mouths of poets, it is not his exploits on the battlefield, his glorious godlike form in all its glory, slashing and hacking, but this moment when enemy and enemy lavish compassion on each other and break bread at the table of grief. The same heart, capable of so much fury, is capable of equal pity. Only the drop of a tear can wash out a drop of blood, salt purifying iron, clear wiping away red. And this drop is shed when we read, and when we remember, and when we grieve.

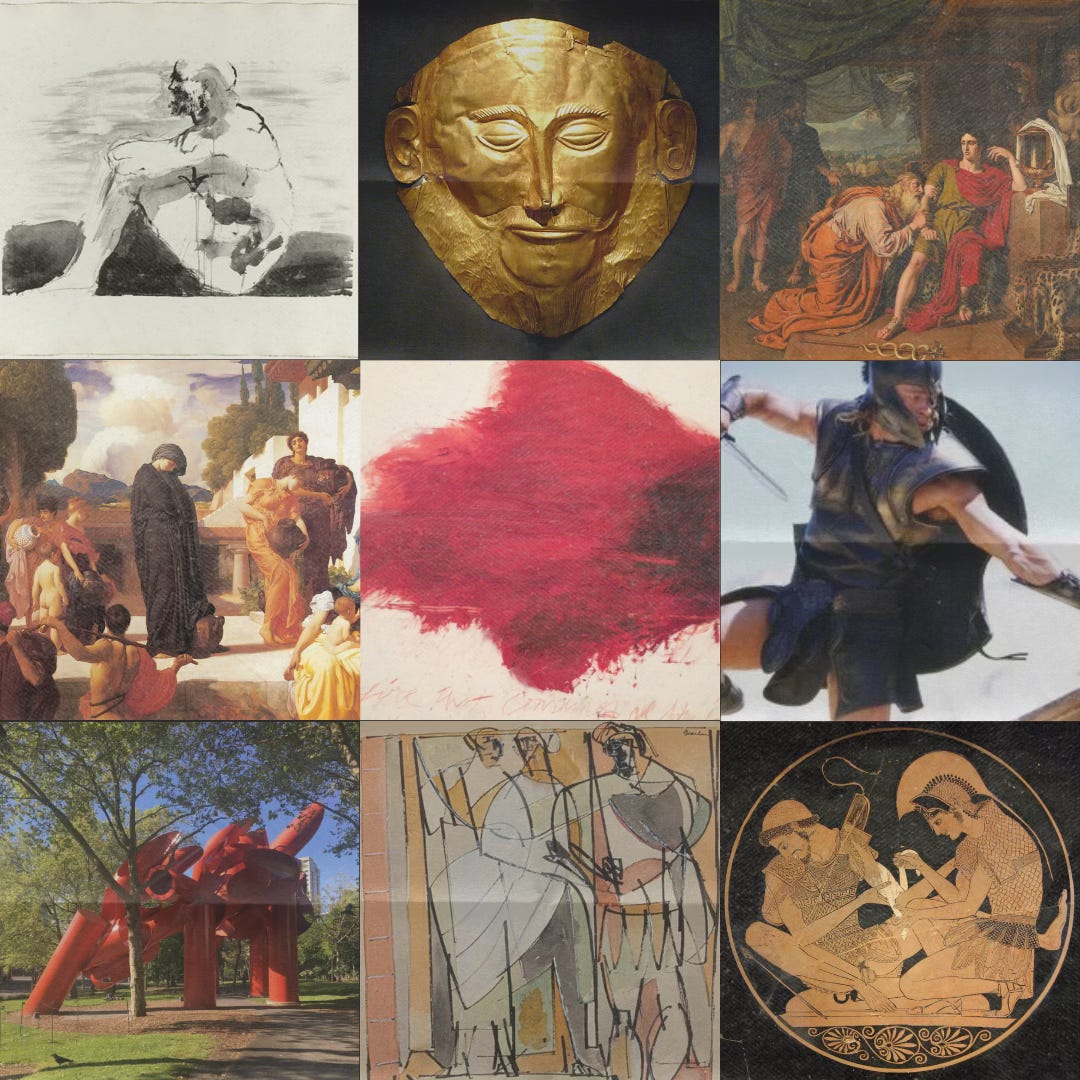

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

Meriden Gravure Company after Leonard Baskin, Achilleus Lay Where the Ships Were, Angered Over the Girl, Briseis, plate 5 from Drawings for The Iliad: American sculptor, draftsman, and graphic artist Leonard Baskin (1922–2000) once said, “Our human frame, our gutted mansion, our enveloping sack of beef and ash is yet a glory…. The human figure is the image of all men and of one man. It contains all and can express all.” Here the human figure is Achilles, as we find him at the beginning of the Iliad, put out like a petulant child because his toy, the slave girl Briseis, was taken from him by Agamemnon.4

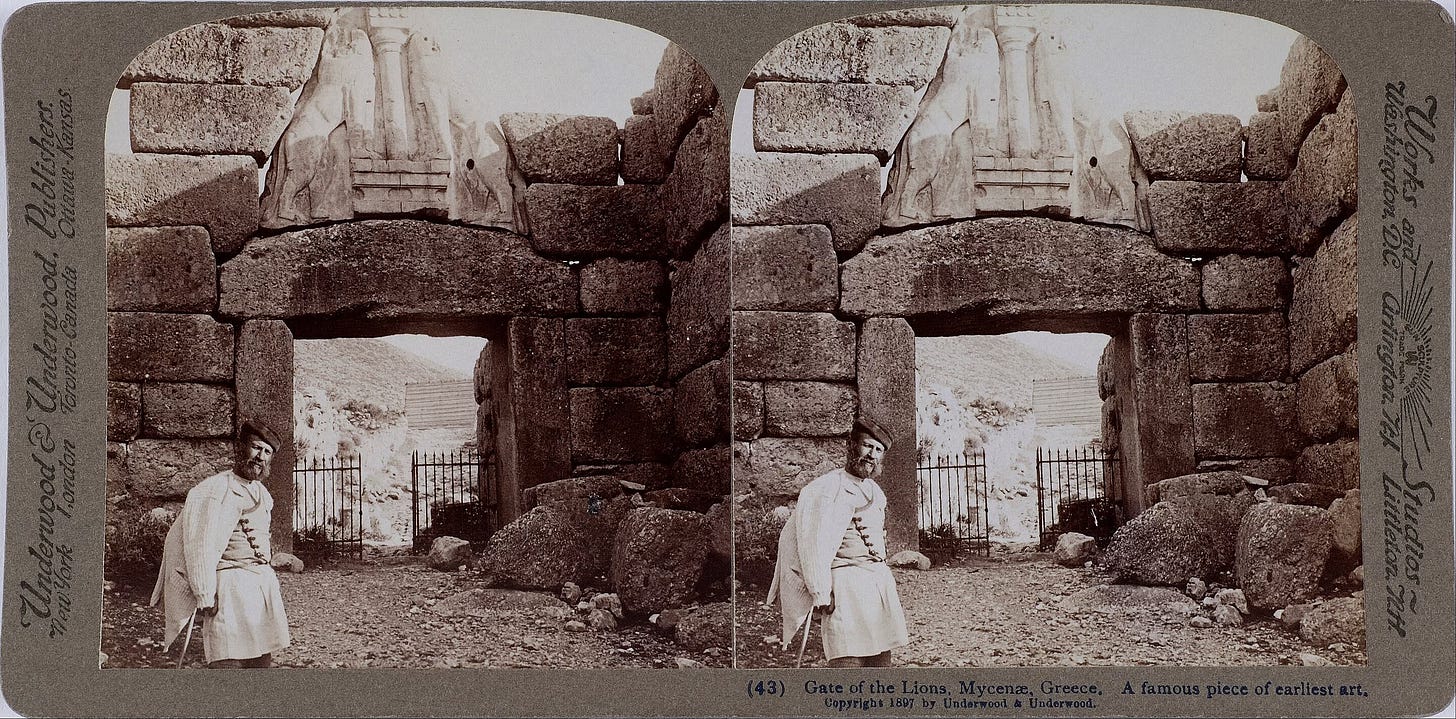

“Mask of Agamemnon,” gold death mask dating to c. 1550–1500 BC: German businessman and amateur archeologist Heinrich Schliemann read the Iliad and the Odyssey as a child, promptly declaring that he would excavate the ancient city of Troy. That he did in 1873, when he discovered the “treasure of Priam” at Hisarlik, Turkey; digging—without permits, proper record-keeping, or adherence to the archeological standards of the day—for what he loved, he destroyed it, a fallout archeologists had to contend with 150 years later. Then Schliemann set his sights on Mycenae, where, unearthing this gold leaf funerary mask in a shaft grave, he exclaimed, “I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon.” Although this has turned out to be more fiction than fact, with modern research dating the mask to about 300 years before the time Agamemnon would have lived, it is nevertheless marvelous, with its curving ears, its coffee-bean eyes, the minutely rendered hairs of its eyebrows and beard, its golden calm and placidity. I got to see it in person last year at the National Archeological Museum in Athens, where you can see countless other astonishing works in gold, utilizing techniques that goldsmiths no longer remember, from a time that has long since passed out of memory.

Alexander Ivanov, Priam asks Achilles to return Hector’s body (1824): Turning against the tide of contemporary art trends, Russian painter Alexander Andreyevich Ivanov (1806–1858) persisted in keeping alive the neoclassical tradition. Here, in a scene rich with color and texture and detail, he uses those techniques to depict the moment when Priam begs Achilles for the body of Hector. The young hero, cloaked in blood-red, leans back from the old king clinging to his arm in a posture of pitiful supplication, reduced from his kingly glory to one who must beg for his son’s body at the feet of his enemy. Achilles gazes at Priam disdainfully, his heart not yet softened, his compassion not yet stirred.

Frederic Leighton, Captive Andromache (1888): Frederic Leighton (1830–1896) is one of my favorite painters, and I love his dreamy depictions of subjects drawn from mythology and history. Here we see Andromache, the wife of Hector, clad in mourning black, standing apart in her grief from the color and activity and men and women and children around her. Her husband has been brutally slain, her young son thrown from the city walls, that city destroyed, and she herself becomes the concubine of her husband’s killer’s son. It is hard to imagine a worse fate to bear.

Cy Twombly, The Fire that Consumes All before It from Fifty Days at Iliam (1978): Cy Twombly (1928–2011) was an American painter and sculptor who was known for an abstract, gestural style of scrawls and scribbles, a line he described as “childlike but not childish,” the “sheer velocity,” as Anne Carson described it, that “takes place on his canvas.” His works often integrated inspiration from literature and history, especially that of the Ancient Greeks and Romans. In 1978, he completed his vast cycle of paintings Fifty Days at Iliam, which is housed in a gallery at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Entering the gallery, one is confronted by red that bleeds from the walls and across canvases, insistent, murderous, heavy with an iron smell. That red exhausts itself into an ash-grey at times, or burns into black, and we are confronted by a din of phallic forms, hot balls of anger, words and names rushing across the canvas like soldiers across a battlefield. Nothing is static here, everything is in motion.

Brad Pitt as Achilles in Troy (2004): War is sad, but the way people die in this movie is really (regrettably?) quite hilarious. When I watched it in one of my classics courses my freshman year of college, we were all in stitches. I don’t know what it is. It probably (hopefully) wasn’t intentional. Anyway, Brad Pitt is hot here, and so is Eric Bana as Hector, and the scene where Priam begs Achilles for his son’s body so he can give him the proper funeral rites is rather touching. Unfortunately, atop a heap of other inaccuracies, this movie is also the source for the quote, “The gods envy us. They envy us because we’re mortal, because any moment may be our last. Everything is more beautiful because we’re doomed. You will never be lovelier than you are now. We will never be here again,” which people keep mistakenly attributing to poor Homer. Now, that’s a crime that just might be inexcusable.

Alexander Liberman, Olympic Iliad (1984): Alexander Liberman (1912–1999) was a Ukrainian-American artist who spent 30 years as the editorial director of Condé Nast; when he wasn’t doing that, he found time to be a painter and sculptor. Many of his sculptures are composed of massive tubes and arcs of painted steel; this one, located in Seattle on the lawn surrounding the Space Needle, is painted red and heaped in a carefully composed chaos. The fun part about a sculpture so vast is that you can walk under it (it is conveniently located above a path) and contemplate it from various angles. Seeing the hollowness of the steel cylinders may have inspired its other name, Pasta Tube.

Romare Bearden (1911-1988), Untitled (from the Iliad series): Romare Bearden (1911–1988) was an American artist who grew up in Harlem during the time of the Harlem Renaissance, and the influences of jazz, folk art, and cubism can be seen in his illustrations, paintings, and collages. Only the second African-American artist to have a solo exhibition at MoMA, he lifted up other black artists, participated in the civil rights movement, and joyfully depicted black culture and community. One of my favorite Odyssey-inspired works is Bearden’s 1977 cycle of 20 collages and watercolors, so I was delighted to learn that in the 1940s, he had made a series of drawings based on the Iliad. The colors here remind me of those found in classical pottery; it’s amazing how simply he captures the vigor and gravitas of these ancient warriors, knitted together in their epic mythos.

Achilles tending Patroclus wounded by an arrow, red-figure kylix, attributed to the Sosias Painter, c. 500 BC: Speaking of classical pottery, I’ve always loved this kylix depicting Achilles tending to the wounds of his companion Patroclus—according to many sources, both ancient and modern, they are lovers, which explains the depth of Achilles’ consuming grief and his even more consuming desire for vengeance when Patroclus is killed. There is so much tenderness in the attitude of the Greeks’ strongest warrior, now gently bandaging the other man’s arm, who turns away, wincing in pain. This cup was found in the archeological site of Vulci, Italy, once an Etruscan city, in 1828, and now lives in the Antikenmuseen of Berlin.

3 Things I’m in Love With This Week

“Iliad, or the Poem of Force” by Simone Weil: Simone Weil writes about force—“the true hero, the true subject, the centre of the Iliad”—and writes with force, her words clanging out like bronze with every powerful stroke. Proficient in Ancient Greek by the age of 12, Weil displays an ease and a facility with the Iliad that enables this force, this power of word and intellect fused together, and she uses her lived experience of war—she fled Nazi-occupied France in 1939—to underscore her idea that force “turns anyone subjected to it into a thing.” However, its subjects are not only those it is used against but those who use it, as World War II, with its horrors of dehumanization, would prove.

Cassandra by Christa Wolf: German author Christa Wolf published Cassandra in 1983; it tells the story of Cassandra, daughter of King Priam and priestess of Apollo, from her own point of view, as she witnesses the Trojan War and the fall of Troy. According to the famous myth, Cassandra, refusing Apollo’s advances, was both blessed and cursed by the god—blessed with the power of prophecy, and cursed so that her prophecies would never be believed. Wolf adds a twist: the reason Cassandra’s prophecies aren’t believed is because she is not even permitted to tell the truth she knows, mirroring Wolf’s own experience of censorship in East Germany and speaking to the silence women have faced in a world where men fight and decide wars. However, my favorite part of the book is not the novel itself but the four essays that follow, where Wolf details her experience of visiting Greece with her husband in 1980. Because of her status as a well-respected writer, she was given an exception by GDR and allowed the rare chance of traveling abroad. I have a special fondness for travel writing, and Christa Wolf navigates the confrontation between Greece as it exists in the dreamy, vague world of poets and classicists, the Greece of proud heroes and shining goddesses, bronze drinking cups and immortal glory, and Greece as she actually encounters it—museums and ruins, headscarf-wearing villagers and dishes of squid and garlic and tomatoes and pita bread—so well.

Memorial by Alice Oswald: Poet Alice Oswald translates the Iliad—but only partially, an “excavation” of bodies, over 200 of them. Everything is left out except for death and a few shining Homeric similes here and there; her mission is to capture the enargeia, the “bright, unbearable reality,” of the original poem. Both the violence of the deaths and the beauty of the similes are blindingly vivid—“He collapsed instantly an unspeakable sorrow to his parents” is one of the most devastating deaths, and “Like when a god throws a star / And everyone looks up / To see that whip of sparks / And then it’s gone” is one of the most spellbinding similes. In her afterword, Eavan Boland writes that Memorial recaptures the oral tradition the Iliad came out of in this way, reigniting its purpose, “which is nothing less than to be an understudy for human memory.”

Words of Wisdom

“The generations of men are like the growth and fall of leaves. The wind shakes some to earth. The forest sprouts new foliage, and springtime comes. So, too, one human generation comes to be, another ends.”

—Iliad 6.146–149, translated by Emily Wilson

The metaphor of the seasons to represent human mortality, human life and death, is common enough in literature, but that doesn’t stop this well-known passage in the Iliad from striking, spearlike, straight to the core. The quote comes from Glaucus, when Diomedes, confronting him on the battlefield, questions him about his ancestry. Glaucus asks him why he wants to know—old generations fall, new generations sprout up again, one after another, and what is the point when they, too, Glaucus and Diomedes, will also wither away and die and fade and give way to those who will inevitably come after? The warriors want so badly to attain immortal glory, for their names to live on despite their bodies’ demise, but there are so many of us, falling from the tree of life one after another, a process as inevitable as the shedding of leaves in autumn, and no more disgraceful.

Poetry Corner

“I saw a man this morning”

I saw a man this morning Who did not wish to die; I ask, and cannot answer, If otherwise wish I. Fair broke the day this morning Against the Dardanelles; The breeze blew soft, the morn’s cheeks Were cold as cold sea-shells. But other shells are waiting Across the Aegean sea, Shrapnel and high explosive, Shells and hells for me. O hell of ships and cities, Hell of men like me, Fatal second Helen, Why must I follow thee? Achilles came to Troyland And I to Chersonese: He turned from wrath to battle, And I from three days’ peace. Was it so hard, Achilles, So very hard to die? Thou knewest and I know not— So much the happier I. I will go back this morning From Imbros over the sea; Stand in the trench Achilles, Flame-capped, and shout for me.

—Patrick Shaw-Stewart

Patrick Shaw-Stewart (1888–1917) was a British poet born in Wales. He went to Oxford, where he studied Classics and was elected Fellow of All Souls College, an opportunity he passed up to become one of the youngest managing directors of Barings Bank. He also joined the “Corrupt Coterie” of Lady Diana Manners, writing her love letters filled with erotic references to Greek and Latin literature. However, his classical knowledge was put to more serious use after the start of WWI in 1914, when he joined the army, later fighting at Gallipoli, where he wrote this poem. It is actually his only poem; though Shaw-Stewart was killed in France in 1917, the poem has continued to keep his name alive over a hundred years later, and I must say that it is my favorite WWI poem.

I love the rhymes between “Dardanelles,” “shells,” and “hells,” and the way that the metaphorical “sea-shells” are transformed into the very real “other shells” of “shrapnel and high explosive,” as well as the way that “hell” is taken out of “shells and hells” to continue into the third stanza and draw a through line between the war that Shaw-Stewart is fighting in and the Trojan War, fought for “Hel(l)-en.”

In the second-to-last stanza, the poem’s speaker directly addresses the mythological warrior who, in spite of all his heroism and strength and wrath and skill and Styx-plunging, also died in battle, and whose death in battle prefigures Shaw-Stewart’s own. The last two lines of the poem reference the moment in the Iliad when Achilles stands in the Greek trench, after learning that his beloved Patroclus has been killed, and Athena causes terrible flames to “cap” Achilles’ head as he shouts his battle cry to the terrified Trojans. Perhaps Shaw-Stewart had a premonition of his own death; Achilles shouts for Patroclus, already dead, and perhaps, too, for all those brave young warriors following fatal Helens to their inevitable dooms.

Beauty Tip

Incorporate more blood-red into your wardrobe, home, and life. What? It’s a pretty color.

Lingering Question

How can you make anger a constructive force in your life?

—

Lovely readers, I hope you enjoyed reading! Please let me know your thoughts by leaving a comment below, and if you enjoyed, like this post and subscribe to Soul-Making for more!

Euripides, Hecuba, translated by William Arrowsmith, from Euripides II: The Complete Greek Tragedies, Third Edition, edited by David Grene & Richmond Lattimore.

Homer, The Iliad, translated by Emily Wilson.

Homer, The Iliad, translated by Emily Wilson.

Agamemnon had had to give up his own slave, Chryseis, after offending her father, a priest of the god Apollo, and experiencing the god’s wrath.

Beautiful article

Ramya,

You brought Iliad alive with this beautiful writing and analysis, choice of van Gogh's painting and Patrick Shaw-Stewart's poem. If I may beg to differ on your beauty tip just this one time :-), I prefer red but not blood-red in my wardrobe! Looking forward to reading your work next week.