Friday Frivolity no. 13: Swans—Ethereal, Enigmatic, Exquisite

The most elegant of birds, in art, mythology, and literature

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a moodboard, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

—

Swans—Ethereal, Enigmatic, Exquisite

The swan, like the soul of the poet, by the dull world is ill understood.

— Heinrich Heine

When it comes to human beings, some of us are graceful, some of us are clumsy; some of us move easily through space, as though dancing or floating, while some of us plod or tread with a heavy, weary pace; some of us are patient, some of us are in a hurry; some of us amble along in a world of dreams and roses, some of us have places to go and people to kill. But who, hearing the word “swan,” can conjure up a picture of anything but grace and tranquility, beauty and serenity? Grace is an inherent property of these amateur angels, a substance, not an accident. It is as easy to imagine a graceless swan as it once was for Europeans to imagine a black one.

Gliding along the still surface of a lake or pond, they seem to move effortlessly, oarless boats, trailing gentle ripples in the water like emanations of divine peace, moving in concert with their own perfect doubles reflected in the liquid mirror. One can almost hear the classical music in the background, a soft stirring of violins, as the coruscations of sunlight on water play upon the undersides of their white feathers and the S-bows of their necks dip and delve. The black and orange of their beaks serves the purpose of a beauty mark, throwing the stainless snow of their plumage into whitened contrast. Like brides, they inhabit a world of perfect contentment, ever new, ever pure, ever fresh. They are the vehicles of Saraswati, Hindu goddess of art and learning, and sacred to Aphrodite, Greek goddess of beauty and love. The arc of their neck is half a heart, and when they mate, it is said, they mate for life.

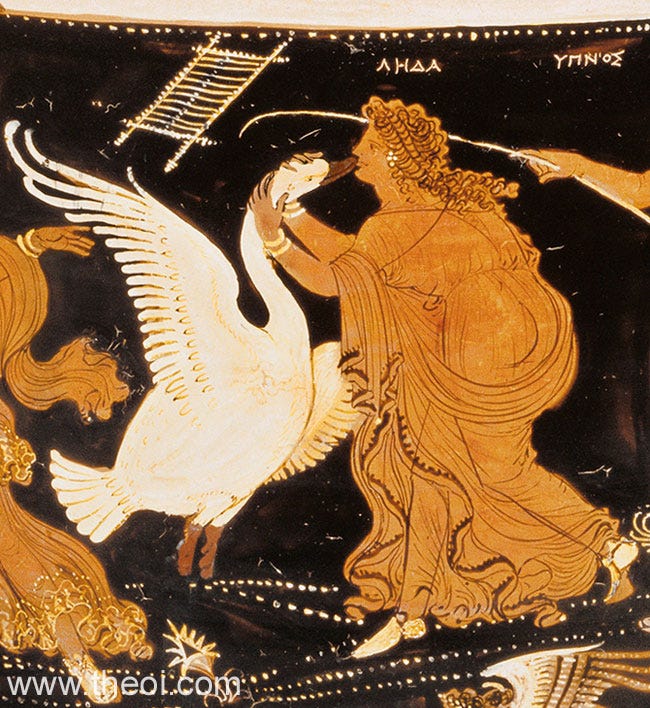

Phaeton, the son of the Sun—that is to say, the god Apollo—went to his father one day, asking for proof that he really was his son. In response, Apollo told Phaeton to ask for any gift, and he would grant it. Like a teenager asking his father to take a precious sports car out for a spin, Phaeton asked to drive his father’s Golden Chariot, the chariot that led the sun across the sky each day. Apollo instantly regretted his oath, but gods cannot renege on their promises. The father’s fears were realized: Phaeton lost control of the reins, drove the chariot towards the Earth, evaporated rivers in Africa, burnt vegetation to a crisp, scorched the land, caused the seas to boil, and prompted the sea god Poseidon to ask Zeus to strike the unfortunate boy down. Apollo, devastated by Phaeton’s loss, handed off the burden of charioting the Sun to Helios. However, he was not the only mourner: Cygnus, Phaeton’s lover, the King of Liguria, abandoned his realm, overflowing the river Eridanus with his tears. To put an end to his laments, Apollo transformed Cygnus into a mute swan. As a swan, Cygnus kept out of the sun and in fire’s opposite, water. He remained silent until his last moments, when he let out in a stream of crystalline melody a dying dirge:1

The silver Swan, who living had no Note, when Death approached, unlocked her silent throat.

The swan became famous for its song, and, though poetic enough in its appearance and way of moving, won even greater favor from the poets through this legend. Ben Jonson called Shakespeare the “sweet Swan of Avon,” and, like the ground that met the chariot driven by Phaeton, the phrase caught fire. Homer became the “Swan of Meander,” Virgil the “Swan of Mantua,” Pindar the “Swan of Thebes,” Anna Seward the “Swan of Lichfield,” and Ukrainian figure skater Oksana Baiul, who skated to music from Swan Lake, the “Swan of Odessa.” However, Coleridge hit on a humbling truth when he remarked, “Swans sing before they die; ’twere no bad thing / Did certain persons die before they sing.”

Given the root of the word “swan” in Sanskrit svana, “sound, noise,” and its similarity to Anglo-Saxon swinsian, “to make melody,” “mute swan” may be a contradiction in terms. Indeed, it turns out that mute swans actually aren’t mute: they hiss, grunt, whistle, snort, and, like Yeats’ wild swans, have “clamorous wings” that throb and beat the air in flight. So, too, is the gentleness of swans a beautiful illusion. As Swiss writer Henri-Frédéric Amiel remarks, “Grace provides protection: as he smooths his feathers, the swan arms himself with a breastplate.” The strongest and fastest of waterfowl, these birds can fight viciously among species; when their mate and cygnets are threatened, they turn savage. In May 2004, a male swan on the shore saw a springer spaniel splashing in a pond, approaching dangerously close to the nest where his mate was sitting, guarding their cygnets. Hissing, he rushed forwards, using his wings to hit the dog. He then took the dog under his wing and held it under the surface of the pond for two minutes, until the poor animal floated up to the surface again, dead.2

Paradoxes and oxymorons: the Roman satirist Juvenal once remarked that, among the vast flock of women, a wife “lovely, gracious, rich, and fertile” was a “rara avis in terris nigroque simillima cycno,” a rare bird on earth, most similar to a black swan.3 The black swan as rara avis soon became proverbial. In 1697, however, the expedition of Willem de Vlamingh to “New Holland” (Australia) brought a European face to face with that supposed impossibility on the waters of what was later christened the Swan River. Three centuries later, Nassim Nicholas Taleb would develop the “Black Swan” theory to explain events that 1) are outliers; 2) have an outsized impact; 3) are rationalized and explained as predictable in hindsight. Such events include World War I and the Internet.4 For better or worse, they transform our world.

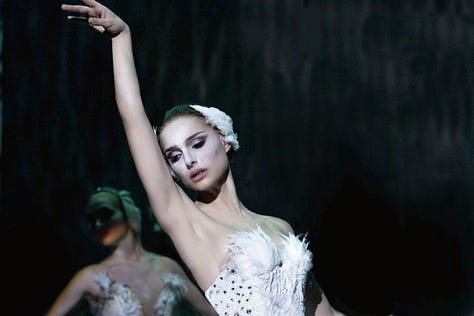

“The black neck arches not unlike / A question mark on the lake,” writes the poet James Merrill.5 If the discovery of black swans made Europeans question their logical propositions, it also raised uneasy questions about purity, chastity, innocence, beauty, and femininity. In Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, the white swan, Odette, is doubled through a mirror darkly in the black swan, Odile. Together, they comprise a dream that can easily be inverted into nightmare, beauty as a mask for badness, virtue vying with vice, madness, fury, passion, envy ever lurking dimly beneath the placid surface of innocence.

In the Henry James novel Confidence, Gordon Wright falls in love with the clever, inscrutable Angela, but his best friend Bernard advises against it. Instead, Gordon marries Blanche Evers, who is described as “simple, trusting, childlike,” “tender,” “pretty,” “young and innocent,” “an article of fantasy,” “deliciously useless,” “kittenish,” “charming,” a creature who “had quite the plumage of a swan, and sailed along the stream of life with an extraordinary lightness of motion.” However, Blanche turns out not to be as stainless as her name—not a swan, indeed, but “a little goose,” and she supposedly has an affair, leading Gordon to lament “the wretchedness of what [he has] found!” So, too, are the women of Truman Capote’s socialite sphere—C. Z. Guest, Slim Keith, Babe Paley, Ann Woodward, etc.—described as “enduring swans gliding upon waters of liquefied lucre.”6 Beautiful, stylish, rich, the doyennes of Fifth Avenue, they seemed to drift in their rarefied circles without even the hint of a breeze to ruffle their perfectly preened feathers. But they gossiped viciously. Their marriages were often unhappy. Paley’s husband cheated on her carelessly and often. Most dramatically, Woodward came under suspicion for murdering her husband, the banking heir William Woodward Jr., before she committed suicide by cyanide poisoning.

Nothing better captures these paradoxes than the many swan stories that center around strange metamorphoses. From Leda and the Swan to endless variations on tales of swan maidens and swan knights, swans serve as the outward guise of divinities or divinely mysterious women and men. For a while, they dwell on Earth, mortal, happy. Then they leave their lovers’ lives as peculiarly as they had come into them. Like ripples on water, only the beguiling memory of their presence remains. The water slows and stills; the last bell-like tones of their melody hang upon the air, dissolve, and fade.

No beauty lasts forever.

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

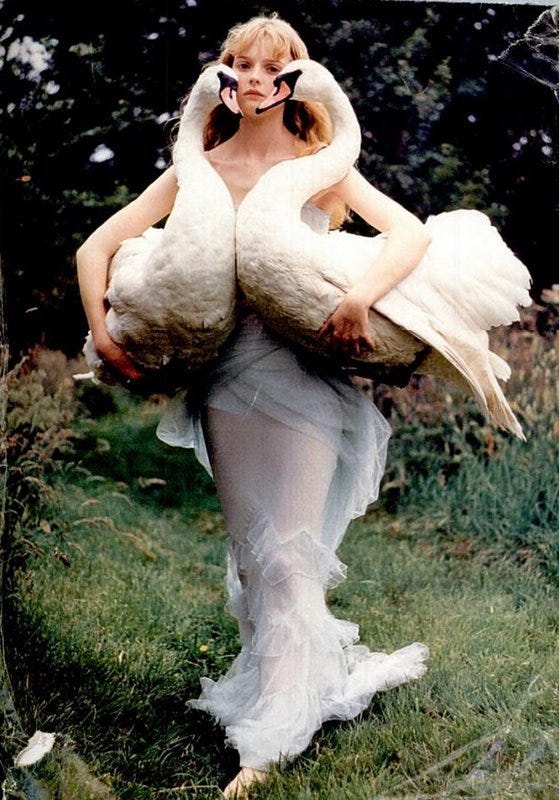

Swan dress by Marjan Pejoski, worn by Björk at the 2001 Academy Awards: Björk was criticized and parodied for this dress when she appeared in it at the Oscars in 2001—one critic said she looked “like a refugee from the more dog-eared precincts of provincial ballet,” while another called it “probably one of the dumbest things I’ve ever seen,” and poor Björk was put on several “worst dressed” lists. Those critics have no sense of whimsy, imagination, or fun. What could be more iconic than Björk bringing an ostrich egg along with her, then “laying” it on the red carpet? She later remarked, “I don’t really know why I’m obsessed with swans but as I said, everything about my new album is about winter and they’re a white, sort of winter bird. Obviously very romantic, being monogamous…. Right now, swans seem to sort of stand for a lot of things.”

Yiannis Gouzos and Petros Themelis, egg sculpture on the Greek island of Pefnos: In the Greek myth of Leda and the Swan, the god Zeus, ever the philanderer, fell in love with Leda, the Queen of Sparta, and seduced her on the banks of the River Eurotas, where she was bathing. Disguising himself as a white swan, he pretended to be fleeing a predatory eagle and sought refuge in Leda’s sheltering embrace. Later that night, she lay with her husband Tyndareus. The two unions resulted in two eggs, from which hatched two sons, the mortal Castor and the divine Pollux, and two daughters, the mortal Clytemnestra and the divine Helen of Troy. Helen of Troy was, of course, “the face that launched a thousand ships,” and the connection of Leda’s story to the ravages of the Trojan War is beautifully compressed into a sonnet by W. B. Yeats, “Leda and the Swan.”

clockwise: Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, Leda and the Swan (ca. 1870); detail of Leda and the Swan (ca. 350 - 340 B.C.) , J. Paul Getty Museum Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931), Leda with Swan; Bertalan Székely, Leda with the Swan (ca. 1880s) In antiquity, on the Greek island of Pefnos, bronze statues were erected of Castor and Pollux, the Dioscuri, as Pefnos was said to be their birthplace. In 2020, Petros Themelis, a professor of classical archeology, inaugurated a new statue, carved by Yiannis Gouzos, on the island, honoring its history by depicting Leda’s union with the swan on a stone egg. The image hearkens back to ancient Greek pottery, while the egg itself gives the work a distinctly modern sensibility, its weathered whiteness harmonizing with the rugged landscape of rocks, waves, and open sky.

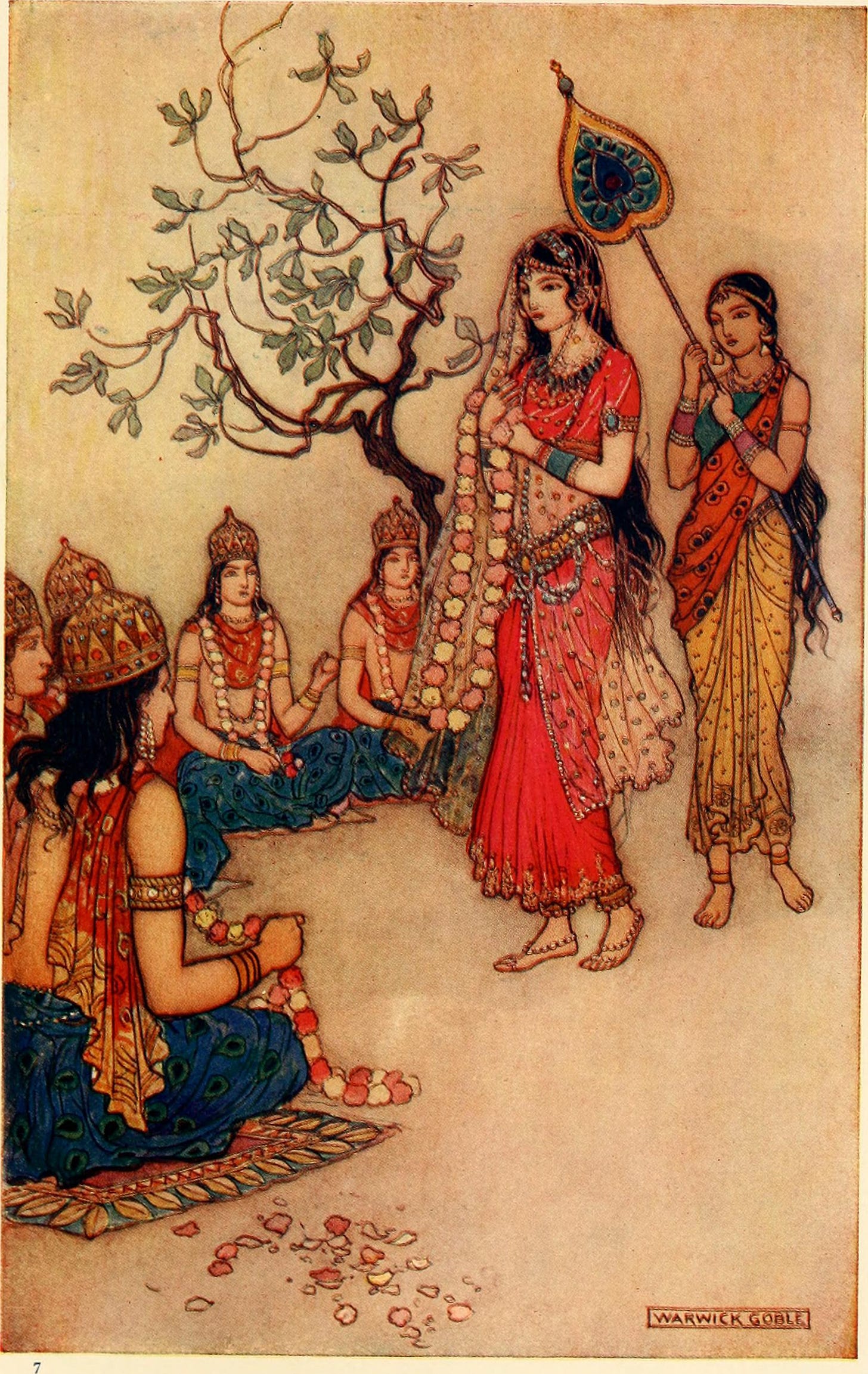

Pefnos islet and egg Raja Ravi Varma, Hamsa Damayanti (1899): Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906) was born into an aristocratic family in present-day Kerala. He studied painting with both Indian and British teachers, and his art seamlessly combines Indian subjects with Western techniques. An ardent admirer of the beauty of Indian women, Varma modeled his depictions of Hindu goddesses and characters from Hindu mythology off of them. This painting depicts Damayanti, a princess of the Vidarbha Kingdom, whose story is told in the Mahabharata. Hearing many around her laud the praises of Nala, the king of the Nishadhas, she grows attracted to him; the same happens with Nala. One day, Nala sees a few swans with golden wings in a grove. He catches one of them, and the swan promises to extol his virtues to Damayanti in exchange for its freedom. Listening to the swan praise Nala, Damayanti falls in love to the point of sickness. Her father decides to host a swayamvara, during which she must choose a husband from several suitors invited to the palace. Seeing her beauty, several gods also decide to vie for Damayanti’s hand, but they first send Nala ahead as their messenger. Damayanti tells Nala she will either marry only him or die. When the gods show up, they all come in the guise of Nala; she says she will only marry the real Nala and begins to pray. Revealing their divine forms, the gods acquiesce, moved by her deep love and devotion. Damayanti and Nala marry, and despite some later trials and tribulations, live out their married life in happiness.

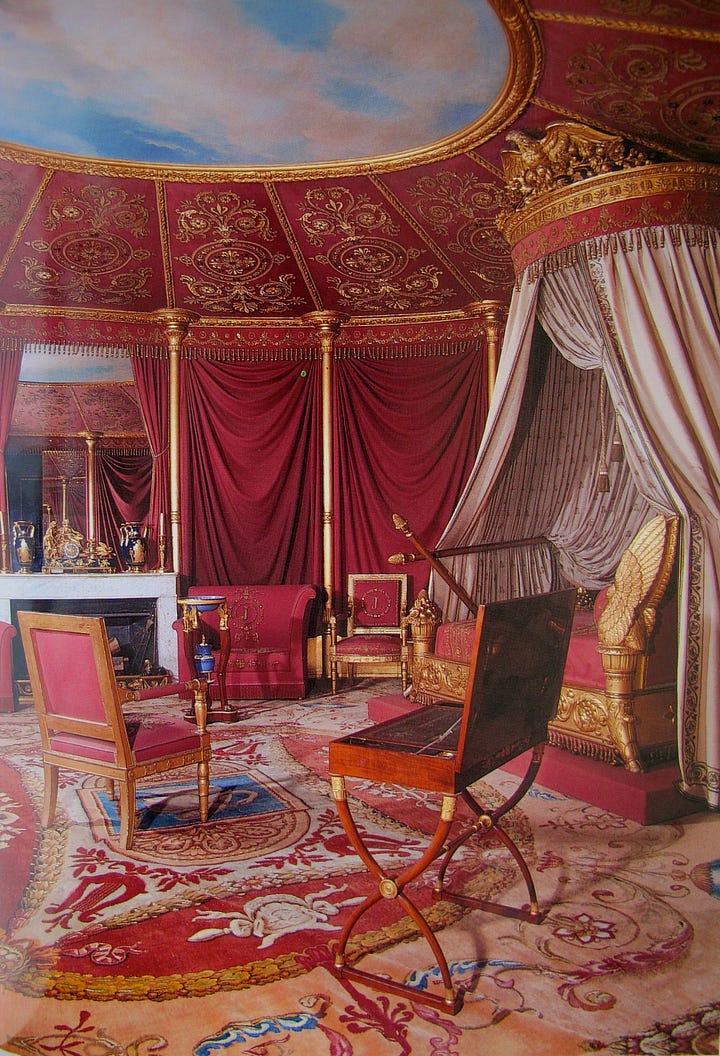

François Gérard, Portrait of Josephine de Beauharnais (1801): The Empress Josephine bought Malmaison, on the outskirts of Paris, for herself and her husband Napoléon Bonaparte, intending it to be a refuge from the hustle and bustle of the city. When Napoléon divorced her in 1810 due to her inability to produce an heir, it became her own refuge, and she spent a fortune refurbishing it. She had plants and animals brought in from all over the world, including rare red-beaked black swans from Australia. Swans were her favorite animal, and she adopted them as her emblem, dispersing their image all over the château as an ornament.

Josephine's bedroom at Malmaison, with swan bedposts and a swan on the carpet; detail of swans on bed; swan armchair; swan cup and saucer Natalie Portman as Nina Sayers in Black Swan (2010): Black Swan has unfortunately been coopted by all the #coquette #lizzygrant #girlblogging girlies on Tumblr, but I still think it’s such a beautiful and psychologically intense film. It centers around Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman), a ballerina with the New York City Ballet, who lives with her overprotective mother. The ballet company is putting on a production of Swan Lake, and Nina auditions for the role in front of the company’s director, Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel). She does well as Odette, the innocent and fragile White Swan, but cannot quite master Odile, the dark and uninhibited Black Swan, who is better portrayed by Nina’s rival, Lily (Mila Kunis). As the pressure for perfection takes a toll on her, Nina begins to lose her grip on reality.

Black Swan (2010) Photograph of swans in springtime via ur-daily-inspiration: I love this image of swans swanning in a profusion of springtime pink, gliding through the fallen blossoms scattered upon the water.

Swan Boat in the Boston Public Garden: The Swan Boats have been an icon of Boston since the 1870s, when it was a popular summer pastime to row small boats on the pond of the Boston Public Garden. In 1877, Robert Paget created a pontoon boat that allowed passengers to sit on benches in the front, while the captain sat in the back and propelled the boat by means of a bicycle-like mechanism attached to a paddle wheel. Robert and his wife Julia loved the opera. They took inspiration from Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin, in which a knight crosses a river in a boat drawn by a swan to rescue a maiden (see the story of the Swan Knight below), and Robert designed the iconic swan to hide the paddle mechanism at the back of the boats. Unfortunately, Robert passed away a year later, in 1878, and management of the Swan Boats fell to Julia, who ran it for over three decades while also raising her four children, making the Swan Boats one of Boston’s earliest woman-owned businesses. Today, the fleet of six Swan Boats are managed by 4th-generation members of the Paget family. The boats run from the second weekend in April to Labor Day weekend in September, and from what I remember, it only costs around $4—a steal for such a magical experience.

performance of Richard Wagner's Lohengrin in Oslo in 2015, sets designed by Kaspar Glarner and costumes designed by Christian Lacroix The Royal Ballet’s Swan Lake (2000), photographed by Alastair Muir: One of the most popular ballets, Swan Lake was composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and premiered in Moscow in 1877. It tells the story of Prince Siegfried, who stumbles upon a group of swans while hunting and falls in love with their queen, Odette. She tells him she and her companions have been cursed by the evil sorcerer Rothbart to transform into swans by day. At night, by the side of an enchanted lake created from Odette’s mother’s tears, they return to human form. The curse can only be broken by true love. Rothbart transfigures his daughter, Odile, to look like Odette, and Siegfried falls for the ploy, pledging his love to Odile instead of Odette. Only too late does he realize his mistake. He runs to the lake, where he passionately apologizes to Odette. She forgives him, but it is too late, and she chooses to die instead of remain a swan. Deciding to die with her, Siegfried also jumps into the lake, and their love breaks Rothbart’s curse over the other maidens and kills him. Together, the lovers ascend to heaven.

Walter Crane, The Swan Maidens (ca. 1894): Walter Crane (1845-1915) was an English painter, designer, and prolific children’s book illustrator who contributed to both the Arts and Crafts movement and the Aesthetic (“art for art’s sake”) Movement. Of all the many mediums he explored, he loved painting the best, and he loved exploring themes from folklore and mythology. Variants of “swan maiden” stories are found in several cultures throughout the world, even in linguistically isolated groups, often featuring women who appear in the guise of migratory birds like swans, geese, cranes, or herons. In the version depicted by Crane, seven swan maidens go to a lake to bathe, removing their swan skins and leaving them on the shore. A hunter comes to the lake to shoot ducks, spies the maidens, and steals the swan skin of the most beautiful, leading her to his cabin to make her his wife. One day, the maiden finds her swan skin, puts it on, and flies away from her husband, rejoining her sisters.

3 Things I’m in Love With This Week

“Two Swans” pendant made of gold, enamel, and diamonds by René Lalique (c. 1900): I wrote about René Lalique, the French jeweler and glass designer known for his beautiful Art Nouveau and Art Deco pieces, a little bit in Friday Frivolity no. 4. There I highlighted one of his glass works; today I showcase this beautiful work of jewelry. Lalique started out making jewelry in the flowing and intricate Art Nouveau style, which combined elegant curves and flourishes with inspiration from mythology (fairies, nymphs) and nature (dragonflies, serpents, swans). This wonderful pendant drapes a delicate curve of water around two light pink swans gliding upon diamond waters. Around them, gilded water lilies bloom by golden lily pads. During the turn of the century, Lalique started to leave jewelry behind for glass and the ornamental excess of Art Nouveau for the streamlined geometry of Art Deco—unfortunately, in my opinion. I would have enjoyed more gilded swans gliding on diamond lakes.

Silver Swan automaton, 18th century, Bowes Museum: This incredible fusion of beauty and precision, art and engineering, nature and machine, swan and clockwork was designed and built by inventors John Joseph Merlin and James Cox in 1773. “Merlin” as a surname for one of the swan’s inventors checks out—watching the silver swan flex and bend its neck over the little silver fish swimming in water wrought of crystal rods, one feels one is witnessing the closest thing we have to magic. Interwoven of 2,000 intricately moving parts, the swan was shown off at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867. Life-sized and high-priced, it couldn’t help but capture the attention of fairgoers such as Mark Twain, who described his experience of seeing it in The Innocents Abroad: “I watched a silver swan, which had a living grace about his movements and a living intelligence in his eyes—watched him swimming about as comfortably and as unconcernedly as if he had been born in a morass instead of a jeweler’s shop—watched him seize a silver fish from under the water and hold up his head and go through all the customary and elaborate motions of swallowing it.”

Pendant in the form of a swan, Northern European, 16th century, The Met: This tiny treasure was created such that the full beauty of its meticulous craftsmanship could only be admired from close up. In other words, you had to be its wealthy owner, pinning it onto your garments or wearing it close to your skin. A cluster of pearl suggests the bird’s cloudlike plumage, while touches of gold bring out the details of its webbed feet, its feathers, and its neck. The Met suggests this swan might have served as a symbol for the Order of the Swan, a chivalric order of princes and nobles founded in Germany in the mid-15th century to honor the Virgin Mary. Its name comes from the story of the Swan Knight, a tale connected to the era of the First Crusade. In its most basic version, a mysterious knight, arriving in a boat drawn by a swan, comes to the aid of a damsel in distress. She is never allowed to ask him his name or where he is from. They marry and have children. Years pass. Her curiosity only intensifies. One day, she cannot help but ask the forbidden question, and her husband sails away in his swan-drawn boat, never to return.

Words of Wisdom

Slow down: it’s the only way to guarantee your immortality.

—Lauren Elkin, Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London

Poetry Corner

The Wild Swans at Coole

The trees are in their autumn beauty, The woodland paths are dry, Under the October twilight the water Mirrors a still sky; Upon the brimming water among the stones Are nine-and-fifty swans. The nineteenth autumn has come upon me Since I first made my count; I saw, before I had well finished, All suddenly mount And scatter wheeling in great broken rings Upon their clamorous wings. I have looked upon those brilliant creatures, And now my heart is sore. All’s changed since I, hearing at twilight, The first time on this shore, The bell-beat of their wings above my head, Trod with a lighter tread. Unwearied still, lover by lover, They paddle in the cold Companionable streams or climb the air; Their hearts have not grown old; Passion or conquest, wander where they will, Attend upon them still. But now they drift on the still water, Mysterious, beautiful; Among what rushes will they build, By what lake’s edge or pool Delight men’s eyes when I awake some day To find they have flown away?

—William Butler Yeats

This is one of my favorite autumn poems and one of my favorite poems featuring swans. While I was walking around a pond a couple of weeks ago, I saw a few swans on the shore, patiently preening their fluffy feathers, totally used to the audience of humans that had gathered to watch the display (they were, however, a little spooked by a dog). I instantly thought of Yeats’ poem and the line “The trees are in their autumn beauty,” and now that it is finally October, I’m so thrilled to be able to feature this. Yeats has many lovely, bittersweet poems about aging, and here the passage of time takes on a special poignancy as the speaker watches for the “nineteenth autumn” the swans he has counted year after year. As they fly away in his mind, one can’t help but think of the departure of the Swan Knight or Swan Maiden from their sometime spouses.

Beauty Tip

Set aside a small part of your day or week to “preen”—that is to say, set your ruffled feathers in order, straighten and clean and spruce yourself up.

Lingering Question

What is one thing you can be more graceful about in your day-to-day life?

—

I know this one was rather on the long side, but thank you so much for reading if you made it this far!! I hope you all have a lovely weekend. <3 Please like this post if you enjoyed, subscribe to Soul-Making, and leave a comment to let me know what you think!

lines below by Orlando Gibbons

See Taleb’s book The Black Swan (2007) for more.

from “The Black Swan”: https://thepoetryplace.wordpress.com/2012/07/25/the-black-swan-by-james-merrill/

As quoted in C. Z. Guest’s obituary in The Times: https://www.thetimes.com/article/c-z-guest-60g300bjk3t.

This is such a beautiful article.

To cover so many different angles and references in one concise piece is a very difficult task - but you manage it absolutely flawlessly.

Plus, I absolutely love that Yeats poem too.

Keep up the amazing work. I will look forward to reading more of your essays.

WoW Ramya! What a great piece on a little bird swan!!! I love your extensive research, references from time period as early as 18th century. This piece reads so scholarly. "Given the root of the word “swan” in Sanskrit svana, “sound, noise,” and its similarity to Anglo-Saxon swinsian, “to make melody,” “mute swan” may be a contradiction in terms", Yes, it is this contradiction in thoughts, outlook and actions that makes human beings so unique right? May be next time you may elaborate on this. In a business context Nassim Nicholas Taleb wrote a book - “The Black Swan" that talks about the impact of unforeseen events and the importance of being prepared for them. There is an element of predictability and control and how we rationalize after the fact. Just adding my two cents to your scholarly article.